Toyota’s e-CVT multi-tasking hybrid drive is efficient, mechanically simple and electronically complex, and it fits into a small, neat package

Drivers may bemoan the CVT gearbox’s notorious droning, but the advantages make the headache worthwhile

Toyota’s umpteenth incarnation of the Corolla is now on sale, mainly in Hybrid form. It’s billed as having an ‘e-CVT’, which at first had our news antennae all a-quiver.

In fact, e-CVT is simply another marketing moniker for essentially the same hybrid driveline concept Toyota came up with in the 1990s for the first Prius and has stuck with ever since. Originally called the Toyota Hybrid System (THS), it then also became Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD), giving a nod to the fact that it was also used by Lexus and even sold to a couple of other car makers.

Swapping cogs, gear changing, shifting: whatever your favourite expression, gearboxes and cars go together like sticky toffee pudding and custard – unless it’s a CVT. Some drivers loathe the way a CVT’s soaring engine revs are disconnected from the car’s rate of acceleration – known as the ‘rubber band effect’.

The CVT was made famous by DAF when it launched the first production version, the Variomatic, in 1958. Instead of a complex box of cogs, it consisted of two pulleys of continuously variable diameter, connected by a belt. To give the lowest ratio (like first in a manual), the engine-driven pulley is at its smallest diameter and the second pulley, driving the wheels, at its largest.

As speed increases the engine-driven pulley gets bigger and the drive pulley smaller, increasing the ratio – so the car speeds-up. Controlled not by a computer but by a vacuum, it continuously and automatically adjusts for hills and harder acceleration or cruising. The design has been used by many manufacturers over the years, including Audi, Ford and Fiat.

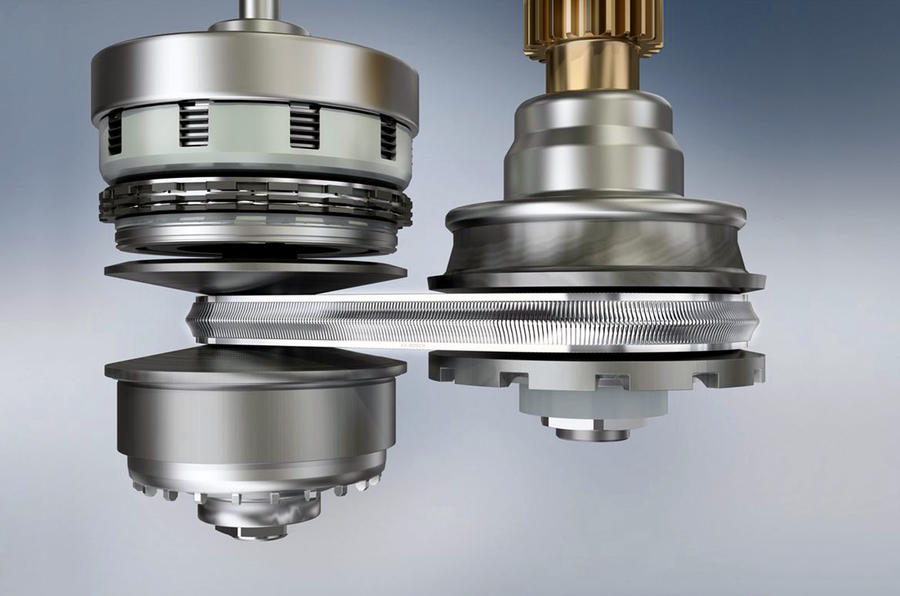

CVTs are not all alike, though. Although Toyota offers a CVT in the new Corolla (but not in the UK), its hybrid drive e-CVT is nothing like the original Variomatic and there’s no belt. Instead, it consists of two electric motor-generators (MG1 and MG2) connected to a planetary gearbox. The whole caboodle has the engine at one end and the driven wheels at the other.

Planetary gear sets exist aplenty inside conventional automatics. The compact package consists of a sun, planets and an enclosing ring gear and resemble a desk toy of the solar system. There are only a few components, but making the drive take different routes through the mini solar system allows the two motor-generators to perform different roles.

MG1 can start the engine and at other times act as a generator to charge the hybrid battery. MG2 can act as a drive motor on its own or with the engine and also a generator to perform a regenerative braking role. MG1 can also apply small amounts of torque to the gear set to control the balance between the engine and electric drive from MG2, and there are many more combinations. The system allows electric-only drive by decoupling the engine (without the need for a clutch), and it’s small and compact.

So not all CVTs are what they seem. This latest one is clever and mega-efficient, and it’s not surprising the basic idea has endured for more than 20 years.

Reverse engineering

Bosch’s electronically controlled version of the original CVT remains mechanically simple. Despite CVTs being scorned by some, Dutch rallycross star Jan de Rooy dominated with his DAF 55 and 555s in the 1970s. DAFs were banished to their own category in the annual Dutch backwards racing championship (yes, really, it used to be a thing) because CVTs enabled them to drive as fast in reverse as forwards.

Read more

Under the skin: the technology behind torque vectoring

Under the skin: how turbochargers have evolved

Source: Autocar