You might know what was number one in the charts when you were born, but what was rocking the motoring world?

Six of our writers, young and not so young, hook up with cars of the same vintage to discover the greatest year in motoring history

Can you stop doing this, please?” requested colleague and friend Richard Bremner. He’s got a point. This is the second feature in a year that has involved Bremner and I getting together with some of the younger members of the Autocar team and some iconic cars of varying vintage. It’s fun but it does make us feel rather ancient.

So here we are again. The challenge this time is for half a dozen of us, representing a broad sweep of ages on the magazine, to choose our favourite from cars that were launched in the year we were born. You can now appreciate Bremner’s anxiety, not least because he’s the oldest.

As you will read, the exercise has brought together a truly fascinating line-up of cars; a group so varied that they would be unlikely to appear together in a feature in a classic car magazine.

They’re from a wide range of years, too. Bremner starts us off in 1958, followed soon after by me in 1962 and stretching right up to Simon Davis, who the stork deposited on the earth in 1993. In between, we have Matt Prior in 1975, Matt Saunders in 1981 and Mark Tisshaw in 1989.

The cars are interesting in their own right, but they also mark moments in time and put into context the companies and industry that produced them.

My choice, as you’ll see, and Tisshaw’s, are extremely closely linked despite being 27 years apart in age. Prior’s and Saunders’ cars also narrate a telling tale about the British motor industry, straddling the old world and foreshadowing the new one.

Who out of the six was born in the best year for cars? We’ll be tackling that thorny one, but I’ll tell you right now: from memory and from checking on Wikipedia, I can’t see how Saunders will be able to put forward a case for 1981.

So follow us on this journey back to the crib. I’ll wager that all of you will be poring over the list of cars launched in the year of your birth to see if you’re from a vintage year or one in which the grapes died on the vine.

Richard Bremner – 1964 Aston Martin DB4

Quite surprisingly, the DB4 is the best-known new car that 1958 produced. Well, almost – it’s the succeeding but largely identical DB5 that’s familiar throughout much of the world as the Aston Martin of James Bond. But there would have been no inkling of this at the time. Only 1110 DB4s were produced, the car’s price ensuring it a rarefied clientele and infrequent sightings for the rest of us.

Miles certainly aren’t drawn out in a DB4. This coupé had 240bhp to deploy 61 years ago – massive, compared with the 37bhp of a Morris Minor 1000. Not that sterile statistics make it my choice among the class of ’58. Rather obviously, it’s the exquisite beauty of its superleggera aluminium skin that makes this the irresistible fantasy choice.

Designed by coachbuilders Touring of Milan, its complex construction consisted of a steel chassis, a tubular steel framework from which were hung hand-wrought aluminium panels that with rain and time provide an expensive demonstration of electrolytic corrosion. But the alloy panels also reduced the Aston’s weight, its 1311kg not so bad given the size and the heft of the twin-cam six-cylinder lying beneath its letterbox-scooped bonnet.

In the unlikely event that you tire of admiring the DB4’s just-so lines, opening the bonnet also presents you with a beautifully sculpted cluster of machinery. The low walls of the cam covers that house neatly arrayed spark plug leads, the bell-shaped domes of the twin SU carburettors and the absence of plastic mouldings make this a sight to admire even if you don’t understand the combustive forces that occur within. When it was new, those forces were sufficient to thrust the elegant nose past 60mph in 9.0sec. Slightly disappointing today, perhaps, if scaldingly fast compared with a Minor 1000.

Many of these earliest of DB4s – the Series 1 you see here the first of five mild evolutions – have had their cylinder blocks bored out of necessity, the pistons and liners required to renew them unavailable for decades. The only solution was to expand the engine to 4.2 litres, yielding 280 horsepower, and of more believable strength than the original 240bhp. More realistic, says this car’s owner Bryan Smart, is 215bhp. Despite his installing a longer-legged axle ratio to counter the lack of overdrive, this DB4 bounds away, and will quite effortlessly travel at 30mph in first should you need it. That makes it more than able to keep up with, and outpace, many moderns, providing you master a gearchange that requires a sometimes brutally firm hand to gift first gear. The rest submit more easily, and with rewardingly mechanical engagement once their oils are warmed.

The chassis sometimes feels quite mechanical too, from the resistant heavy steering to a suspension prone to sudden, vintage jerks and geometry that allows topography-induced wander. So you need to pay attention. Paying attention to curves and throttle brings reward too, the Aston’s urge to run wide snuffed out with a keenly – and carefully – applied throttle. It’s swift and satisfying, revealing a car as beautiful in motion as it is when dormant.

One to forget

Edsel: Bremner’s year of birth was quite a good one for new cars, but one launch that still brings out the sweats in car maker boardrooms is the Edsel. Yes, Ford’s ill-fated sub-brand was launched that year. It survived only two years and lost Ford $250 million. And you thought Maybach wasn’t successful…

Matt Saunders – 1981 Triumph Acclaim

My maternal grandfather’s knowledge of the British car industry will always be a matter of supposition to me – but you’re looking at evidence to suggest that he knew it well enough when it mattered. When the time came, in September 1981, for George Sandford to buy an affordable saloon to ‘see him out’ – the very last new car he would ever buy – he bought a Triumph Acclaim. Not a Ford, a Vauxhall or an Austin, but the UK’s very first Japanese transplant. And see him out it duly did, before going on to do a whole lot more besides.

George got something else that year as well: a second grandson who would eventually inherit his sage purchase, still going strong and with less than 30,000 on the clock, at the not-so-tender age of seventeen. I then used the Acclaim to ‘see out’ my A-levels and my university degree, and even to start work at the age of 21. I also put Hella spotlights on the front bumper and a pair of six-by-nines on the back shelf (sorry, Grandad): items that, I was disappointed to note, don’t feature on the British Motor Museum’s example, although it’s otherwise wonderful.

You can probably appreciate why picking a birthday car didn’t take me long. It’s not a flash one; nothing to hold a candle to Bremner’s gorgeous DB4 or Goodwin’s fanciable Lotus. But then 1981 was bit of a desert for the introduction of interesting, world-beating passenger cars. When Google turned up the news that the Acclaim was introduced in the right year, I was suddenly uncharacteristically uninterested in the Maserati Biturbo or Lamborghini Jalpa that might have stood in for it.

The Acclaim was a car that didn’t sell in chart-dominating volume and didn’t attract the attention of enthusiasts like its immediate rear-driven forebear, the Dolomite. Some will tell you it was Triumph’s lowest ebb: a rebadged Honda Ballade used as a stopgap by British Leyland, with just enough UK-sourced content to count as ‘locally produced’. It filled a gap for BL in the early 1980s, in the build-up to the launch of what was expected to be a world-beating, all-new mid-sized hatchback: the Maestro. Like it or not, though, the Acclaim was significant. It was how Japanese car design and production techniques first had an influence on UK car making. Without that influence, volume car making on these shores would have died a death a long, long time ago.

The Acclaim was rightly celebrated for reliability, setting record lows for warranty payouts for BL. We had a Hillman Avenger before Mum took on Grandad’s Acclaim: a typical example of how UK volume car making had been. It broke down fairly regularly, wore twice as quickly, had much less room in it, leaked and stank (either of damp upholstery or exhaust fumes, depending mainly on the weather).

The Acclaim must have been like a revelation for its owners by comparison: it was comfy, compact, well-packaged, drivable, economical and pretty refined. You might say that it was the beginning of the redeeming modernisation of the UK car industry. But here’s the plain truth: if my grandad had bought almost any other British-built car in his price range back in 1981, I reckon I’d have been getting the bus to my Post-modernist Literature seminars in 2001. And since you can’t offer lifts to girls when you’re on the bus, I was very grateful that Grandad George chose so well.

One to forget

Maserati Biturbo: Harsh, but I’d say the Maserati Biturbo would be one to forget from 1981. It certainly would have been if you’d bought one new then. Air-cooled turbos had a habit of cooking their oil and seizing up. Plus the car’s styling didn’t do justice to the badge. Not if you were old enough to remember cars like the Ghibli and Bora.

Mark Tisshaw – 1989 Mazda MX-5

Think 1989 and you picture Japan. Not only for the cool gadgets that were emerging at the time – from Game Boys and pocket-sized mobile phones to robots that supposedly could clean your home/make your job redundant/run off with your wife – but for the country’s coming of age as a maker of cars you craved for more than just build quality and reliability.

This was the year that Honda revealed the NSX, a supercar to rock the establishment and prove that the breed could be usable as well as breathtaking to drive. Toyota and Nissan, meanwhile, launched luxury brands in Lexus and Infiniti to show it could make cars to compete at the sharpest end of the global car world (okay, we’re still waiting for Infiniti to do that…). Elsewhere, Mitsubishi and Subaru gave us signs of the exciting things to come in the decade ahead with the 3000GT and SVX.

The 1989 Japanese Grand Prix was about as memorable as they come, too, with Alain Prost ‘turning in’ on his McLaren team-mate Ayrton Senna at the chicane at Suzuka to seal the world championship.

And then there’s the car you see before you: the Mazda MX-5. The story of the MX-5 is so well told, I won’t repeat it in detail, as you already know what it’s all about: front-engined, rear-wheel drive, convertible roof, affordable price, brilliant handling, accessible performance… all adding up to a sports car formula that feels as right today as it did back then.

Along the way, it’s often been imitated but never bettered – you know when you’re onto something when every other car maker’s attempt to take you on is known as an ‘MX-5 rival’. Few other cars can claim a similar billing: 911, 3 Series, Defender, Golf. What that group also have in common with the MX-5 is an appearance in our recent Icon of Icons feature, where we aimed to pick the car whose significance has been unsurpassed in the automotive world. Of the cars assembled here today, just the MX-5 was on that shortlist, as it’s the only one whose appeal has endured and that has remained relevant beyond the time at which it was conceived.

Japan, of course, wasn’t the only place in the car world where stuff was going down in 1989. Quite literally in the case of the Berlin Wall, whose demise began the process of reunifying Germany and allowing its national car makers to think bigger and look further afield than ever before. Also going down was our industry back home, where British Aerospace’s taking of what was British Leyland into private hands a year earlier led to the creation of the Rover Group that had only Rover, MG and Land Rover left as its brands. It was also the year that Ford bought Jaguar, having purchased Aston Martin two years earlier.

While other national car industries were growing in strength and expanding their horizons, Britain’s had become fragmented. The MX-5 was the type of car Britain should have been creating to successfully build on the Lotus Elan and others of the 1960s, yet we’re all grateful Japan picked up where we left off.

One to forget

Aston Martin Virage: Without question. Dull styling, very average to drive and not very well made. I had the suspension collapse at 150mph on Millbrook’s high-speed bowl. It staggers me how much money they fetch today. Give me a Jaguar XJ-S any time.

Colin Goodwin – 1962 Lotus Elan

Well that’s a good start. I’ve only been alive for eight weeks and we’re going to have a nuclear war. Or it certainly looked like we might as warheads were on their way to Cuba on Russian ships. At least while Nikita Khrushchev and John F Kennedy were playing out their deadly chess game, I was blissfully unaware. I was also in the dark about another frightful situation closer to home: neither of my parents had a driving licence. At this stage it wasn’t a big issue, but it would later become one.

But while the world was about to self-destruct and I was destined to spend the first 17 years of my life on public transport, there was good news elsewhere. It was a terrific year for car launches. We could open with the birth of the Ferrari 250 GTO, but that was virtually a racing car. Most were road-registered and competed in events like the Tour de France, which included long distances on public roads. The GTO was, however, hideously expensive.

No, the standout launch of 1962 for me was of the Lotus Elan. The MGB and Triumph Spitfire were also unveiled this year, but the Lotus is a league above and is considered by Gordon Murray the best sports car yet made (he owns two and has never been without one). Like the GTO, the Elan was made by a company that was born to race and only sold road cars so that it could do so.

The Elan we have here has been lent to us for the day by Paul Matty, the Midlands-based Lotus guru who has been supported for many years by Steve Cropley (who only recently posted off a fat cheque to Matty for a Lotus Cortina). This Elan, recently bought by a very lucky customer, is a jewel. The Elite that went before it was groundbreaking for its glassfibre monocoque, but it was expensive to make and didn’t turn a big profit for Lotus. The Elan, with its steel backbone chassis and glassfibre body – designed by Ron Hickman, who was later the father of the Black & Decker Workmate – was a profitable car. I’m not sure if this Elan was factory-built or made from a kit (many were, to dodge purchase tax). It has been restored since and Matty has just fitted a new chassis to it.

This car is tiny. When launched, it weighed 640kg and crept up to 674kg as it became the S2 in 1964. The first cars were simply called Elan 1500 (of which only 22 were made) and then Elan 1600. Our car is actually an S2, but you’d have to be sharp to tell it apart from a ’62 car. A few days ago, I was driving a new BMW 8 Series. Wide, heavy and a steering wheel so fat, I could hardly wrap my fingers around it. Contrast against the Elan’s delicate wheel, itself connected to the most sensitive and accurate steering ever fitted to a car. This is the thing about the Elan: if you drive one today, you wonder where it all went wrong.

Well, we didn’t all go up in a mushroom cloud. The Elan took to the world’s race tracks, giving Paul Newman his first racing experience, was owned by ’60s icons Peter Sellers and Noel Redding, and finally ended production in 1973. In 1987, my mum got her driving licence, aged 59, and I started work at a motoring magazine. Within the next five years, I will own an Elan. I’ve promised Paul Matty.

One to forget

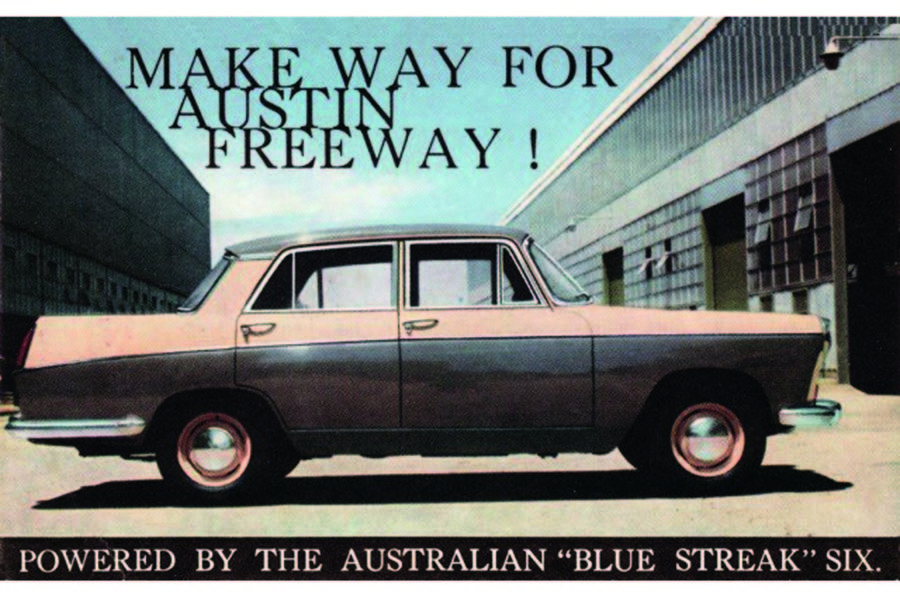

Austin Freeway: Honestly, it was a fantastic year. I’ve had to delve quite deeply to find a duffer and it’s required going to Australia to do it. I give you the Austin Freeway, an Aussie version of our A60 Cambridge. I did many miles in a Cambridge as a kid and even then I thought it was horrible

Matt Prior – 1975 Triumph TR7

Ah, the mid-1970s and the British automotive industry in crisis, churning out more than its share of spudders. Contributor Bremner is bound to have owned some of those, I joked to Goodwin.

Turns out he still does. This is his Triumph TR7, a car so radically styled that on seeing it at the Geneva motor show, it’s claimed designer Giorgetto Giugiaro walked from one angle to another and said: “Oh God, they’ve done it to the other side as well.”

A good yarn, if true. Or even if not. But it’s not the only way the TR7 raised eyebrows at its 1975 launch. It replaced the TR6, a six-cylinder drop-head with independent rear suspension, but only sported a four-cylinder motor and a live rear axle. And a roof. Sophisticated it wasn’t.

Partly Triumph opted for simple mechanicals so the TR7 would appeal in the US, the car’s biggest market. In fact, while the TR7 was launched in the US in 1975, to meet demand there it wasn’t made available to UK buyers until the following year.

That American focus is one of the reasons the TR7 looked the way it did, too. Incoming roll-over crash protection legislation appeared that it might outlaw convertibles for good in the US (though it never did), so the Triumph was designed with high roll-over protection in mind. Its rakish body also incorporated America’s impact bumpers more neatly than some rivals.

That gave the TR7 the appearance of a mid-engined sports car – perhaps a problem given it was no such thing when the Porsche 914 and Fiat X1/9 were – while its 2.0-litre eight-valve engine, even in 105bhp form (federal emissions regulations meant it produced considerably less in America), was no match for a contemporary Ford Capri.

A mildly disappointing British product of 1975, then, that may not have improved with time. I empathise entirely.

Nevertheless, the TR7 sold rather well – the best-selling TR ever, in fact. Its development team, led by Spen King, were known for making cars more than the sum of their parts and, despite the mechanical drawbacks, the TR7 was considered, by the august publication you’re reading now, as quite adept on country roads. Previous TRs had better engines than chassis. This had the opposite.

I sink into a surprisingly agreeably appointed cabin. The TR7 has good visibility – although I’ve managed to break a door mirror before even setting bum inside it (sorry, Richard) – and not a bad driving position.

It cruises nicely, too, I find on the M40, spring sunshine warming my head through the sunroof, and it has low cruising noise levels and a torquey engine. On more challenging roads, it’s softly sprung by today’s standards – what isn’t? – but there’s fun to be had. It’s compact, absorbent but composed enough, steers well and shows a decent balance.

In its time, the TR7 wanted a better engine and, in the form of the V8-powered soft-top TR8, which was reserved for the US only, it got one. The UK TR7 convertible remained a four-cylinder. Then, after six years and having been built in three different factories, with sophisticated rivals outclassing it and no replacement lined up, production ended. Which means Bremner’s tidy red TR7 is perhaps more appealing now, as an odd but mildly charming curio, than it was in the early 1980s.

One to forget

Hyundai Pony: While the AMC Pacer is an obvious candidate for the title ‘Runt of 1975’, it’s actually too interesting a car. Well, it is compared with the Hyundai Pony. It was South Korea’s first mass-produced car and obviously didn’t make much of an impact on the world stage. Just you wait, said Hyundai.

Simon Davis – 1993 Fiat Coupé

I actually used to own a Fiat Coupé. Admittedly, it was on the Gran Turismo 3 video game and I would have been about nine or 10 at the time, but I remember it distinctly. It was yellow, just like this one, and it completely changed how my young mind perceived the Fiat brand.

You see, Fiats were a rare sight when I was growing up in New Zealand. What would become the hyper-popular reimagined 500 was yet to be, well, reimagined, and I hadn’t been educated on the likes of the 124 Spider and the X1/9. In fact, the only Fiat I was aware of at the time was the first-generation Multipla. And seeing one of those for the first time didn’t make for a particularly favourable formative experience.

The Fiat Coupé, on the other hand, taught me that Fiats could look great – even in pixelated, digital form on a television screen. And you know what? I think it still looks great today – although not quite as glorious as Richard Bremner’s DB4 – some 26 years after its original reveal in 1993.

Penned by Chris Bangle, and with an interior designed by Pininfarina, the Coupé might not have been the purist’s sports car of choice, owing to its front-drive configuration. But a limited-slip diff helped ensure it was still a sharp-handling steer. It was a quick one, too. Originally, it came with a 2.0-litre, 16-valve four-cylinder Lampredi engine that in turbocharged form developed some 187bhp. Five-cylinder engines were introduced further down the line, and saw power rise as high as 217bhp.

This one, however, makes use of the Lampredi unit. It might not be as sophisticated as the engines of today, but there’s a special type of pleasure that comes from driving cars with older turbocharged motors. This one is no exception.

Initial pick-up is smooth and brisk, but as soon as the tacho needle strays past 3500rpm and the boost has built up, the surge of additional acceleration released is hilarious. It’s not as brutal as it might be in an old Evo or Impreza, but it still feels fast. It corners well, too, while the gearbox is light and reasonably snappy in its action. Admittedly, the driving position isn’t amazing (for me, anyway), and this one’s brakes perhaps aren’t as effective as they once might have been. Regardless, driving N96 LAP confirms the opinion I held as a child: the Fiat Coupé is an awesome little car.

Of course, the Coupé isn’t the only iconic car to have been launched in 1993. There was the 993-series Porsche 911 and its GT2 sibling; the Lister Storm with its 7.0-litre V12 derived from that used in the Jaguar XJR-19 race car; and, at the other end of the automotive spectrum, the first Mercedes C-Class and the BMW 3 Series Coupe. The Aston Martin DB7 made its debut in ’93, too.

Not a bad innings, really.

One to forget

Seat Cordoba: Quite a few duffers to choose from, but the Cordoba was a particular dullard. We had a long-termer for a year and I don’t remember ever sprinting for the keys. I’d forgotten it existed until I wrote this.

So what was the best year ever?

It’s 1962. How could anyone argue against it? Great Britain still ruled the motoring world. Well, a bit of it. An important bit, in fact, because cars like the MGB and Triumph Spitfire put hundreds of thousands of people behind the wheel of a cheap, half-decent sports car.

Another legend broke ground in ’62: the Ford Cortina. We had to wait a year before Colin Chapman waved his wand over it, but even humble versions were good cars.

If they were a bit mundane for you, how about the AC Cobra? Yes, it was a joint effort with the US, but it’s still an iconic car.

Read more

Aston Martin DB4 GT Zagato: reborn classic headed to Le Mans

Greatest car flops of all time

Source: Autocar