Use of aluminium for the chassis saved weight

Resurrecting Land Rover’s icon is nothing new, as we discovered when we met the man behind the 1997 LCV2/3

An icon in its own lifetime, the original Land Rover and later Defender was always going to be a hard act to follow. Many concepts have come out over the years to suggest what a future Defender might look like, but there have also been a few lesser-known projects within the company that did produce actual running prototypes. One of these experimental vehicles currently resides in the British Motor Museum, less than a mile from where it was born at what is now Jaguar Land Rover’s Gaydon engineering site.

Finished in 1997, this little red pick-up called Lightweight Concept Vehicle, or LCV2/3, was constructed out of unused parts from an earlier LCV2 prototype. It was finished in time for a demonstration drive with Dr Wolfgang Reitzle, who at the time was boss of product development at BMW, the company that kept money in the meter of Rover and Land Rover during the mid to late 1990s.

But the purpose of this quirky vehicle was far greater than just to impress the top brass. It did, in fact, have many far-reaching benefits, many of which can be seen to this day, as Peter Wilson – who joined the team as project manager for Experimental Vehicles in 1995 – explains: “We looked at forward production techniques five to 10 years down the line, to evaluate how they could be fed onto the production line. We were also demonstrating the ways and means of reducing weight in production cars.”

Here’s what we got: 2020 Land Rover Defender officially revealed

Initially, the first LCV car – LCV1 – was, according to Peter, “an attempt to knock weight out of a Discovery just by substituting aluminium for steel. The problem was you needed to use heavier section aluminium to maintain the strength of the steel one, so it was a bit of a blind alley.”

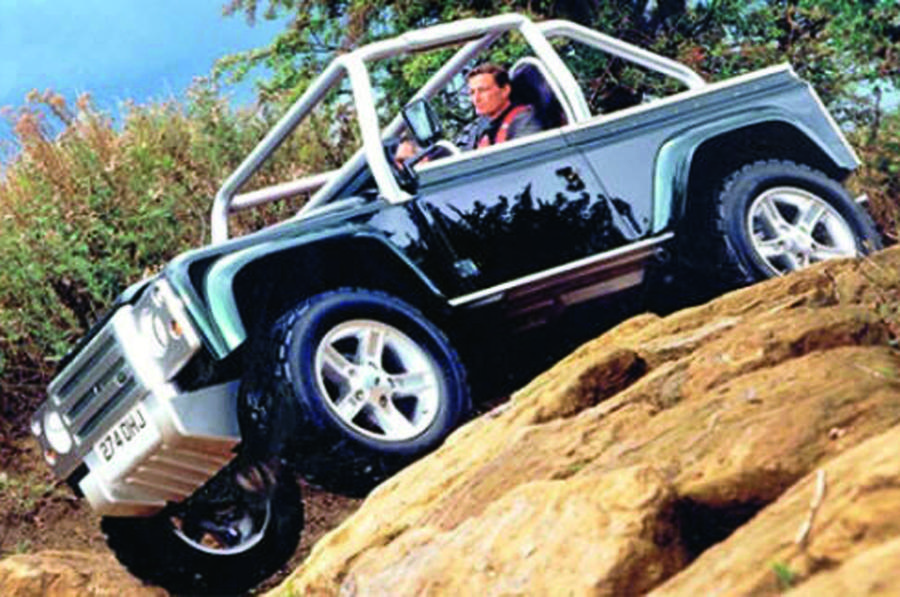

LCV2 was a much more successful venture that ditched the separate chassis for a spaceframe made of extruded aluminium to save around 400kg compared with the standard vehicle. In the finest traditions of prototype disguises, LCV2 looks just like an ordinary Defender. Only the most determined anorak would spot the slightly lower roofline.

LCV2/3 carried on a number of technologies from its predecessor but introduced bent extruded aluminium that would allow for a more rounded, aerodynamic shape (0.45Cd against the 0.66Cd of the production car). It was stuck together with both epoxy and Corabond adhesive along with self-piercing rivets – not entirely dissimilar to how Jaguar Land Rover sticks its cars together today. There was some thoroughly modern technology under the skin too, such as an innovative traction control system that could mimic a locking differential by braking a spinning wheel to send power across to the one with traction. It first appeared on a production Land Rover with the second-generation Discovery, and nearly every SUV since has used a similar system.

The team also managed to include synchromesh on the low-range gearbox so you could operate it on the move, LED rear lights and a clever sliding three-passenger bench seat. A KV6 petrol engine powers this particular prototype, so it could reach 60mph in a rather rapid (for a Land Rover at the time) 8.8sec.

And it all worked remarkably well. Aside from the composite panel around the rear window that didn’t fit properly – and required the shop steward to turn a blind eye as Wilson and the team made it fit – it was actually more capable off road than the original thanks in no small part to the lightweight construction.

It no doubt impressed Reitzle, because he went to see it and the experimental division first during his visit, as Wilson recalls, before heading off to the styling department in the car.

Unfortunately, no matter how impressive the technology was on these LCV cars, events outside the project’s control conspired against the enterprise. In 1998, BMW had been in discussion with Rover trade unions over a rescue deal with the promise of major cost savings from the British side. Suddenly, the funding for a group of renegade engineers working out of garage 117F behind some petrol pumps in Gaydon didn’t seem like the most prudent use of money, even though, as Wilson claims, they didn’t spend their entire allocated £8 million budget.

Wilson took voluntary redundancy a little while after the project was wound up in the latter half of 1998. He tried to get the experimental vehicles and the valuable project drawings into a museum as an educational feature but was usurped by BMW. As Wilson puts it, the German company “wanted to examine the aluminium technology we’d used in much more depth for the upcoming Rolls-Royce project”.

I ask what it was like leaving the Rover Group and he pauses: “It’s a bit like getting off your ship and waving goodbye to all your pals as it sails out of the harbour, then someone torpedoes it”, referring to the collapse of MG Rover in 2005.

It is perhaps a sad end to what was a promising project. However, some comfort can be sought in the fact that, of the four running prototypes and three crash test chassis, two vehicles from the project still remain: LCV2/3, which can be seen in the Collections Centre of the British Motor Museum, and the earlier LCV2 that now lives in the Dunsfold collection. And although neither car directly influenced the successor to the Defender, if you consider the specification of the new version, it’s remarkable to think that the experimental team was on the right path some 20 years ago.

Who knows what else could have come out of the project if it were allowed to continue? Wilson and the team can be proud of the part they played in the legend of this iconic Land Rover, and the fact that their work lives on to this day.

Other attempted Defender replacements

1991 Challenger

There were three running prototypes in the Challenger programme: two station wagons and a military-style pick-up – the latter being the only survivor. Built on a Discovery chassis, it was deemed too complicated by the military and die-hard fans hated the looks, so the project was canned.

1999 SVX Concept

Revealed at the 1999 Frankfurt motor show, this was a highly updated Defender with traction control, hill descent control and cross-axle differential locks – although none of this actually worked. The massive 20in wheels and custom-made tyres also compromised the turning circle.

2011 DC100

Another concept based on Discovery underpinnings was the DC100. There was a stubby threedoor estate and even an open-top version with a V8. It had many features on it that have since found their way into production JLR products, such as the waterproof leisure activity key.

Read more

New Land Rover Defender: icon reborn as tough upmarket 4×4

The epic story of the Land Rover Defender

Land Rover Discovery: driving the original 30 years on

Source: Autocar