The view’s great, but how useful are roads like this one for tuning?

From snaking B-roads to cobbled ride-testers, the UK has an unrivalled variety of surfaces that car makers exploit to fine tune their creations

What makes an ideal road for tuning, where do Britain’s top chassis developers go to find the best ones and what influence do they have on how a car drives? To find out, we spoke to several veteran car testers and engineers.

Andrew Unsworth, head of vehicle dynamics, Bentley

Looking at the whole performance envelope of cars like ours means seeking out a very wide variety of roads. We need to assess ride comfort throughout the speed range, even beyond 150mph in our case. We need big primary ride inputs at times and sweeping bends for steering tuning. Loops are good – and we have a few – so we can keep driving the same corners and over the same surfaces to judge changes we’ve made.

One of our evaluation loops starts at the factory gates at Pyms Lane in Crewe, quickly takes in a road with a changing surface that’s deteriorating in places and then has A-roads and B-roads with truck grooves. We have an unofficial agreement with the local council not to resurface it, and one of the reasons it’s so handy is that senior managers can get a feel for a car during sign-off without travelling very far.

A bit further afield, there’s a loop we use in the Peak District that I like. It’s a sort of triangle of roads starting at Buxton and passing Bakewell, Leek and Longnor. It has surface changes, sunken ironwork and a mix of bigger and smaller topographical features. That’s probably where I would choose to go with, say, a final prototype. But we use North Wales plenty as well, particularly en route to and from Anglesey Circuit, which we also use for dynamic development.

In the early project stages, our cars spend almost all of the time on track, but by the end of a project, the total development time is probably 50/50 road and track. With the road miles, more of them are probably done away from the factory than close to it – but UK roads are definitely a factor in defining the capabilities of our cars.

We have great variety in the UK. It’s something Volkswagen Group engineering colleagues always say when they come in for a driving day, and I don’t think Bentley would make quite such great GTs if we didn’t.

David Pook, consultant vehicle dynamics expert

Every company is different, but I don’t think many have prescribed reference testing routes. In my experience, the best and most useful roads for testing are the ones you know absolutely. Some of the assessments you’re making and the impressions you’re getting need to come from inputs you make almost subconsciously. There’s a parallel you might make with relationships. Some people say there’s one person for everyone; I think you find a person you like and then come to love them because you know them so well.

The Gaydon area is blessed with some amazing roads that don’t really go anywhere. In my Jaguar Land Rover days, I could be on what I call my steering route within five minutes of leaving the factory gate. I’d head towards Kineton down the B4100, then go via Gosport Lane and Edge Hill. I’ve driven it so many times that I know everything about it, so I can be confident when, say, I’m driving the same car for the sixth time in a day, having made almost imperceptible changes to it, that the impressions I’m getting are valid.

Then there are the occasions when you go looking for roads you don’t know and unexpected situations you need to respond to. Driving is about both acting and reacting, and you learn so much more about a car in a dynamic environment.

I do believe the cars of particular brands are to some extent a product of the roads around where they’re engineered. First of all, UK roads are different to those elsewhere; we all know that. If you do too much work abroad or in other parts of the country and the car no longer works when you get home, it’s a problem – you just end up chasing your arse.

I was at Jaguar when the chassis development team moved from Whitley to Gaydon. It happened in 2005 but, if you didn’t know that, you could probably work out when it happened, because the ride and handling of the cars subtly changed.

Mike Cross, vehicle integrity chief engineer, Jaguar Land Rover

Using a wide variety of roads and environments is absolutely key to thoroughness in what we do. One road, no matter how amazing it looks or how challenging it feels to drive it, is never going to give you everything you need. People in our line of work spend much longer in urban environments, in traffic and on craggy harsh surfaces, than we really do on idyllic Welsh mountain roads.

We tend to get the car working in and around Warwickshire before we evaluate it in North Wales and then over in Germany. And when we go to Wales, we use some of the same roads as I guess Autocar does, out of Ffestiniog and around Welshpool. But every change we make elsewhere is then checked and verified back in Warwickshire, because you don’t want the pursuit of any one target or characteristic to skew the whole compromise and positioning of the car.

The particular roads around Gaydon certainly have an influence, yes, but I reckon we would end up with a very similar car even if we did most of our road driving elsewhere.

Being based in mid-Wales certainly sounds interesting. You can learn an awful lot about a car on a wet Welsh B-road, I always think. The more experienced you become in what we do, the less tied you feel to particular routes and reference surfaces. You learn to pick out the important traits in similar roads that happen to be conveniently placed when you need them, and so you very seldom need to travel 150 miles to be sure about a particular problem or characteristic.

With the proving ground at Gaydon there for the really punishing high-speed stuff, the extreme roads you might picture aren’t the ones I often seek out when I’m tuning steering feel or handling response. It’s the narrower ones with the closer high walls or hedges, where visibility is limited and you feel really hemmed in. Those put really high premium on fine handling precision and close body control, which can be very informative.

Matt Becker, vehicle attribute engineering chief, Aston Martin

I’ve gone from Norfolk with Lotus to Silverstone [where Aston Martin uses the Stowe Circuit for dynamic chassis tuning], and the nearby roads are actually quite similar. There’s a decent mix of surfaces, but it’s all pretty flat. The trouble is that you don’t get enough vertical forces into the car to properly test body control.

We used the ‘Evo Triangle’ in North Wales for a while, but that has effectively become impossible now. I couldn’t name them off the top of my head, but there are still roads in mid-Wales that give the great variety of corners you need to fine-tune steering feel and chassis balance, as well as vertical elevation change. If I could move our base anywhere, it would probably be there. We could simply seek some craggier surfaces for the nastier ride-tuning work.

I’m not sure there could be one ideal road for tuning everything, because we work in stages, targeting and tuning specific attributes and seeking roads that allow us to focus on those attributes before moving on. Spending too long in one place is a mistake, because you find you have to undo half of what you’ve changed.

With the number and complexity of the adaptive systems on our cars, we need an even wider variety of dynamic input to really test them than ever before. That’s what leads us all over Europe, not just to Nardò [Italy], the Nürburgring [Germany] and Idiada [Spain] but also to a lot of different kinds of roads in between.

We start with the fundamentals of the vehicle in the same way I always did at Lotus, but we have to cover a lot more ground before the job is done.

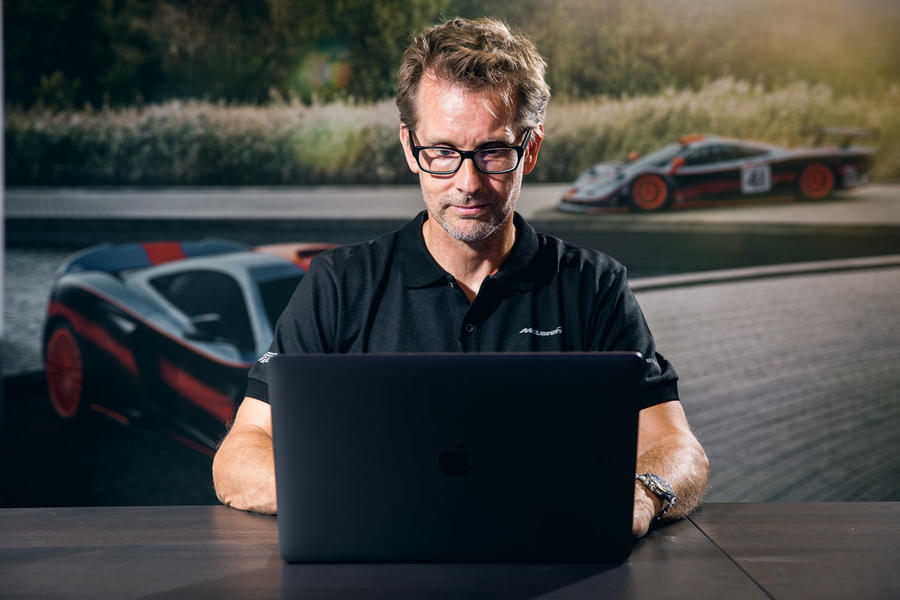

Kenny Brack, chief test driver, McLaren

The speed range of our cars is mostly what defines our approach to dynamic tuning. If you need to evaluate and develop a car up to a top speed of 250mph, you can’t do it in the UK. But you do need to be able to do it somewhere – and it’s as important to do it on derestricted autobahn, where it’s safe to, as anywhere.

We do use UK roads, but mostly because they’re the worst roads that McLaren customers are likely to use; they’re a sort of abuse test. As we know, they’re so bumpy and undulating, with switching on-off cambers – even motorway surfaces are bad. So perhaps they’re not a kind of baseline canvas for us in the way they might be for other car makers, not least because our customer base is so global. If we focused too much on the UK, our cars probably wouldn’t work as well elsewhere.

I probably don’t know UK roads as well as some of the guys you’ve spoken to, because I’ve only lived here later in my life, but that does give me a useful global perspective. I feel very much at home here, though, and I do know plenty of Welsh roads and useful roads in central England.

Like other firms, we have reference roads for tuning particular systems and attributes, but they’re as likely to be in Spain or Germany as the UK. You have to know your key real estate in this business; structure and repeatability in what you do is key.

Every McLaren car, even a Senna or an LT, spends a lot longer on the road than you would think, having the minutiae perfected and being made to feel as good as it can feel. We will always produce cars tuned to appeal to human drivers; the fine detail is so important.

I would agree that roads do define cars, to a point, but possibly not like they used to, back when American land yachts would ride so well on US highways but terribly elsewhere. Today, with the technology and outlook we have and the movement of people throughout the industry, we operate in such a global context; the picture has changed for everyone.

Gavin Kershaw, attributes and product integrity director, Lotus

The roads we tend to use aren’t beautiful or fast. You don’t have to commute for three hours from the factory to get to them – and that’s important, because if a car is doing something really badly, if the suspension is jumping up and down when you brake or the steering centring isn’t right, you’ll know about it very quickly. But if you don’t address the problem straight away, you acclimatise to it, start driving around it. Eventually, you may forget all about it.

Much of the first-stage work we do is based on feedback you can pick up around the factory; we call that yard comfort. How well does the car deal with drain covers, speed bumps and broken Tarmac at low speed? You’ll know whether you’ve got something 80% right almost straight away.

After that, we have a mixed road route out of the factory gate, made up of the same roads used by Roger Becker and John Miles way back when. If you drive out of the factory at Hethel and head towards the A11 via the B1135, you’ll find constant-radius corners with good surfaces that are great for tuning steering connection feel, yaw centre feel and roll behaviour.

From there, if you drive towards Ketteringham Hall, you’ll find what we call our shake road, which is where we tune for harmonic resonance. Even though it’s dead straight, it can feel like it’s pulling a car apart at less than 50mph.

There’s a big crest on Hethersett Road [out of East Carleton] that we call Puttnam’s Leap. It’s a big compression where we can get a car to go from 1.5g of compression to full rebound to check it can keep its wheels on the ground properly.

There’s Spooner Row, back near where I live, which is great for testing asymmetrical suspension inputs, head-toss tuning and kinematic steering feedback tuning. And there’s the Old Buckenham Airfield road, which is four miles long and full of sinusoidal wave inputs that just naturally upset an underdamped car.

We know these roads are ideal, because we see other manufacturers coming all the way to Norfolk to use them. And when you set up a car to work well on them, it will work anywhere – from the Nürburgring to North America.

Richard Parry-Jones, consultant vehicle dynamics expert

I can’t help the engineer coming out in me when I talk about this stuff. If you want to do whole vehicle development, you need a test route – usually a loop of particular roads – that allows you to assess acceleration and braking performance on the x-axis, as well as ride along the car’s y-axis and handling and steering on the z-axis. You won’t be able to take one car after another and get a full picture, assessing all of the effects of any incremental changes you’ve made, unless you can do all three.

I look for fairly sinuous minor A-roads or good B-roads that are wide enough for two cars to pass but not so wide that you can begin to cheat on them – that is to begin to read the road several corners ahead and move some of the dynamic onus away from the vehicle to respond well by soaking it up yourself. There are plenty in Wales, near where I live, and plenty on the North York Moors, for instance. But you can find them in most places. I knew plenty when I was working for Ford in Essex.

A good testing road needs ride undulations of both short and long wavelengths. It should have visibility limited by those undulations and by vegetation, so that it keeps your investment of contemplative and intuitive effort as the driver in balance. If it’s too tight, you’ll be too busy; you need time to read and absorb the responses of the car to your inputs.

Good clear white lines always help, because you can easily judge whether you’ve ended up quite where you intended on the road. But I like stone walls, too: they keep you honest.

Then, if I want to zero in to tune particular things – to do steering refinement, for instance – I find that narrow roads at night work well. You can see cars coming from a distance, which is useful, but more importantly, you can’t see the road as clearly, so you can’t anticipate as much. Your control of the car depends much more on the accuracy of the steering itself.

A good engineer should spend 80% of his time on roads that he knows well – but not as well, for instance, as those of his daily commute, so he doesn’t start to cheat on his inputs – and then 20% of it on roads that he doesn’t know at all, to gauge whether the car feels on your side when you’re dealing with things that you really haven’t anticipated at all.

It is, of course, very easy to stick with roads close to your base for the sake of convenience, but if doing that starves you of diversity, you really shouldn’t.

READ MORE

The anatomy of handling: What makes the perfect driver’s car?

Source: Autocar