We invented the road test in 1928. Almost a century later, we’ve just ticked over test number 5500

There are several great reasons to treat yourself to this week’s issue of Autocar, among them our 5500th road test, which just so happened to be on the Audi S3 Sportback.

Not the greatest hot hatchback, it’s fair to say; as you might well already have read. Nor, perhaps, is it even an anniversary worth celebrating. But if only to mark it, I spent a morning in our archive of old issues earlier this week jumping back in time 1000 tests at a time just to see what I would find.

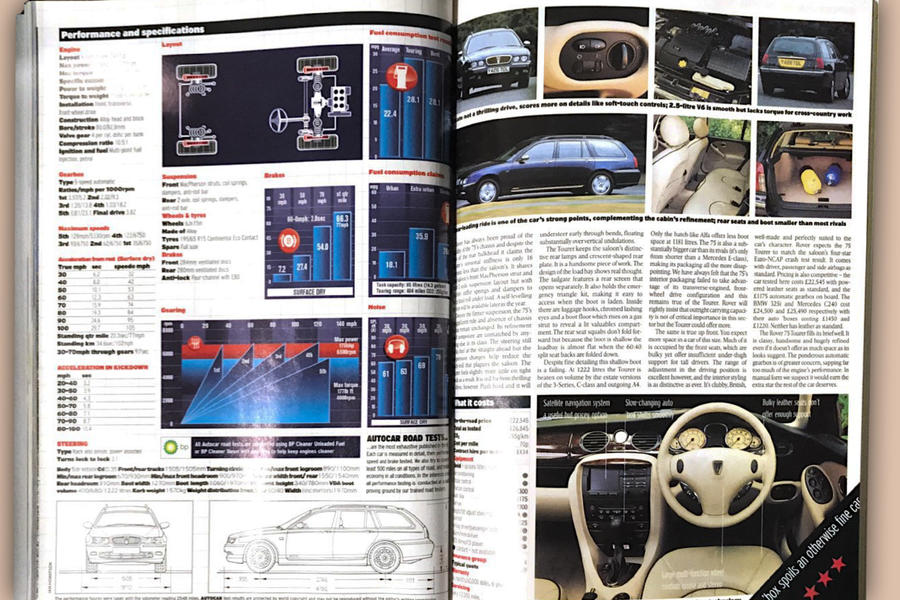

We’re a weekly magazine and always have been, and these days, we generally publish one full road test per issue. Stands to reason that road test number 4500 should have appeared about 20 years ago, then. Back then, we were well into the habit of numbering our weekly big instrumented tests (thank heavens), and so on 4 July 2001, our 4500th road test subject was… the Rover 75 Tourer.

The test came not long after BMW had notoriously sold its ‘English patient’ for just a tenner, and MG Rover was formed. The 75 estate had already been designed by Rover’s former owners, but it became one of the first cars grandly launched under the new era in any case.

We tested the 2.5-litre V6 version, all 175bhp and 1570kg of it. Performance from the KV6 engine was surprisingly weak (0-60mph in 12.3sec) although a hesitant five-speed automatic gearbox from Jatco diverted at least part of the blame for that shortfall away from the lacklustre engine. An oddly shallow and small boot also came in for criticism.

But it wasn’t all bad news for ‘The Phoenix Four’ (remember them?). The 75 Tourer won praise for its “magnificent” ride; for refinement and composure unmatched by anything else in the class; and for handling estimated by the road test jury to be better than the equivalent 75 saloon’s. I can’t imagine satellite navigation was a popular option: it cost £2300 on a car that wasn’t quite £23k at full showroom price in the first place! Still, John Towers’ company car probably had it.

Moving back in time another 20 years or so takes us into slightly uncertain territory where numbered tests are concerned. Between the late 1950s and mid-1990s, Autocar’s road tests weren’t usually numbered in print. Evidently, someone must have been keeping a tally of them, otherwise we’d have had no idea about the milestone we’ve just passed, or any other; but whoever it was is sadly no longer incarcerated in the dungeons of Autocar HQ with only a torch, a notebook and ballpoint pen.

Sometimes, issues in the 1980s and early 1990s wouldn’t have a solo road test at all, running instead with an instrumented comparison as the headline test; sometimes, there would be more than one. But reckoning back from the closest numbered test as accurately as I could brought me to Autocar’s issue of 14 May 1983, when we ran the ruler over the E28-generation BMW 525e.

This was a car with plenty of modern resonances. Running a 2.7-litre version of Munich’s much-regarded straight six fitted with the smaller-ported cylinder head from a 520i, it was designed for greater accessible torque and better fuel efficiency than other Fives. It didn’t have a downsized turbo engine or hybrid assistance but, rolling on 14in wheels and weighing little more than 1300kg, it stood every chance of being a pretty efficient big saloon in any case.

The standard-fit four-speed auto ’box probably wouldn’t have helped its cause. Even so, our testers recorded 34.1mpg out of it during touring economy testing, which must have seemed frugal indeed in Thatcher’s Britain. It got from 30mph to 70mph in less than 10sec, too – and all for a whisker under £12,000.

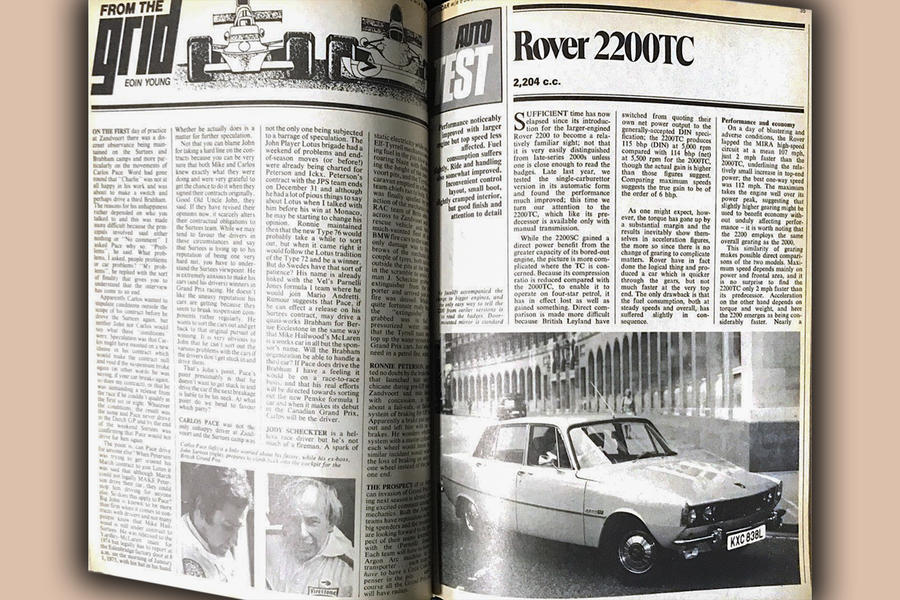

More dead reckoning was required to find road test number 2500, the nearest numbered neighbour being in the late 1960s. I must have got pretty close with, by chance, another old Rover. Our road test subject on 5 July 1974 was the Rover 2200TC, a very late Series II P6 produced under the British Leyland era with the hope of cleaning up the car’s running credentials for export markets.

The TC was an initialism to declare the car’s twin SU carburettors to the world. That, I’m told, is what counted for excitement at the time. They gave the car a monstrous 115bhp and made for better performance than the 2.0-litre predecessor, but slightly poorer fuel economy, according to our testing.

Even in 1974, this Rover P6 was a car with 17in wheels, disc brakes all round and inertia-reel seatbelts. It also had a de Dion rear axle and worm-and-roller-gear steering. And yet it did not escape me that it still managed 0-60mph more quickly than the Rover 75 Tourer we tested more than a quarter century later (11.4sec).

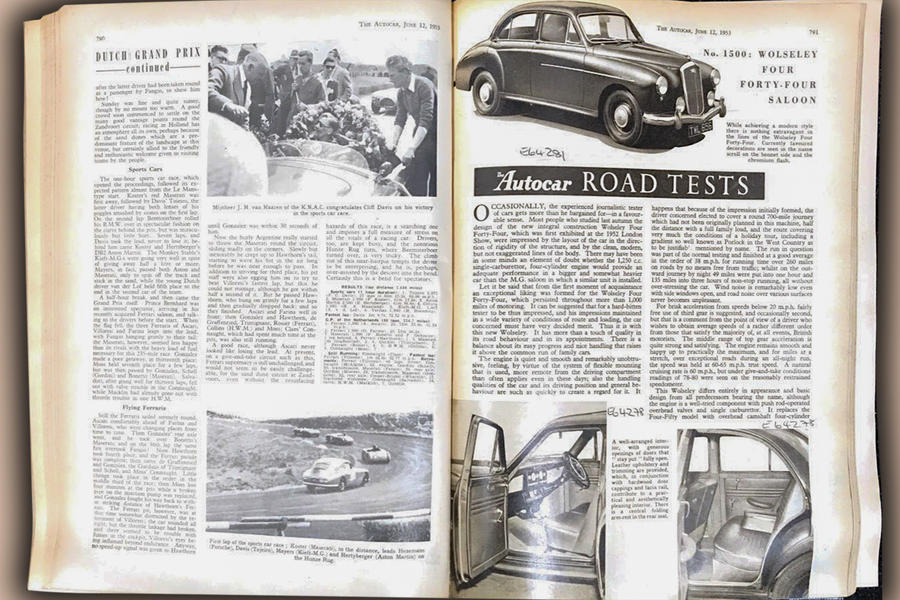

There can be no argument about the subject of Autocar road test number 1500, clearly numbered as it was in our issue of 12 June 1953 (hooray!). Come on down, then, the Wolseley 4/44. This was one of the first post-war, middle-market saloon cars built with a monocoque chassis; our testers called it ‘integral construction’ at the time. It had a live rear axle, drum brakes and a slightly weedy 1250cc engine making only 46bhp – in a car weighing 1128kg as tested. (What are we always told about old saloon cars being really light again?) Needless to say, it wasn’t quick: 0-60mph took 32.6sec.

Even so, the test jury rated it. “From the first moment of acquaintance,” the story opens, “an exceptional liking was formed […] for a car of very decided merit. One with more than a touch of quality in its road behaviour and appointments, a balance about its easy progress, and nice handling that raises it above the common run of family cars.” We didn’t give cars star ratings at the time, but it seems reasonable to assume that this Wolseley’s would have been more than averagely glittering if only it had received one.

Going back in time still further means jumping over the Second World War, during which testing was suspended, and then groping amidst more numbering murkiness. Back in the 1920s and 1930s, the magazine’s editors were quick to drop ‘The Road Test’ completely when there was an important motor race or show to cover; but in other issues, as many as two tests of new cars, and two more of used ones, might appear. Meanwhile, whether any particular test was numbered or not seems to be mostly by luck of the draw.

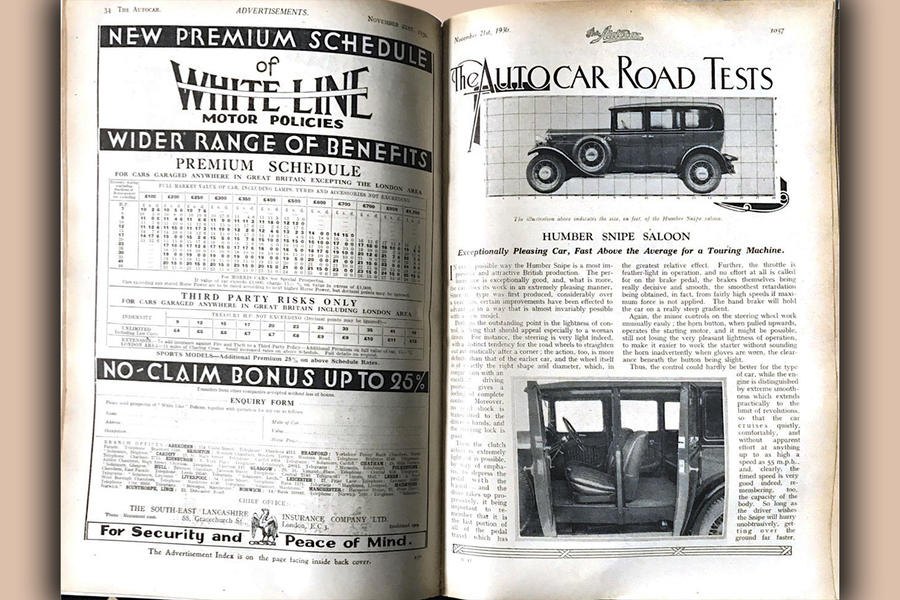

There are just enough numbered ones to suggest, however, that road test 500 happened around the turn of 1930, about when we were appraising the handsome Humber Snipe (21 November 1930), so maybe that was the one. This 3.5-litre, six-cylinder, 1524kg, 24-horsepower saloon, like the Wolseley, was certainly a favourite of the road test team because it seemed outstandingly easy to drive for its time; a quality we reward richly in family saloons to this day.

“In every possible way the Humber Snipe is a most impressive and attractive British production,” the test records. Performance is described as “exceptional”; the car could cruise quietly at 55mph and climb a 1-in-4 gradient in second gear quite comfortably. “So long as the driver wishes, the Snipe will hurry unobtrusively,” the rich praise goes on, “getting over the ground far faster, curiously enough, than the occupants of the car may realise at first, and with plenty in reserve.”

Most rare of all, though, was the Snipe’s “lightness of control, which should even appeal to a woman driver.” Now there was a novel idea. “The clutch is so light it can be depressed with the hand, and there is a distinct tendency for the wheels to straighten out automatically after a corner.” Modern drivability characteristics, then (today we simply call that ‘self-centring’, and only the least driver-friendly new cars don’t have it).

Which brings us right back to prehistoric times as far as road testing is concerned. On the basis of this evidence, I wonder, is it fair to casually suggest, as readers’ letters still frequently do, that we magazine testers only care about fast, expensive, inaccessible and irrelevant dream cars? Because it seems to me that Autocar testers are more interested in modestly powered, British-built bank managers’ saloons.

The truth about the job of the Autocar road tester is that if you can’t root out interesting things to record about cars that many would regard as quite dull actually, you won’t last a month in employment. Sometimes it’s for us to cover the cars we might all wish to own rather than those we’re really likely to – but the balance historically is definitely in favour of the latter. And wherever we look, we’re here to cast an objective scrutineer’s eye, and simply to salute accomplishment and criticise mediocrity wherever it presents. Few of the cars we test are all good, just as few are all bad. But almost none is genuinely boring – and I, for one, believe that electrification needn’t change that.

READ MORE

Autocar at 125: landmark covers from the magazine archive

90 years special: the history of Autocar’s road test procedures

Source: Autocar