Medical equipment production line took some getting used to

The coronavirus has brought out the best in the car industry, as we discover

While 2020 has not been a good year, the tragedy of a global pandemic has shown us the best of humanity – through the selfless efforts of countless individuals and groups to help others in the most difficult circumstances.

Phrases such as ‘hero’ and ‘star’ are too often thrown around liberally, but 2020 has shown who they truly are: the front-line NHS and medical workers who have put themselves at risk to treat others, the healthcare professionals who have looked after the most vulnerable, the essential workers who have kept the country running and those who have put the needs of others above their own.

Support for those heroes often came from unlikely areas. As lockdowns ground the car industry to a halt, many of those involved in it turned to help tackle Covid-19. Car companies and their staff made and donated PPE, helped develop and build vital medical equipment, delivered care packages and more.

Here is a selection of stories showing how the car industry helped in the face of adversity.

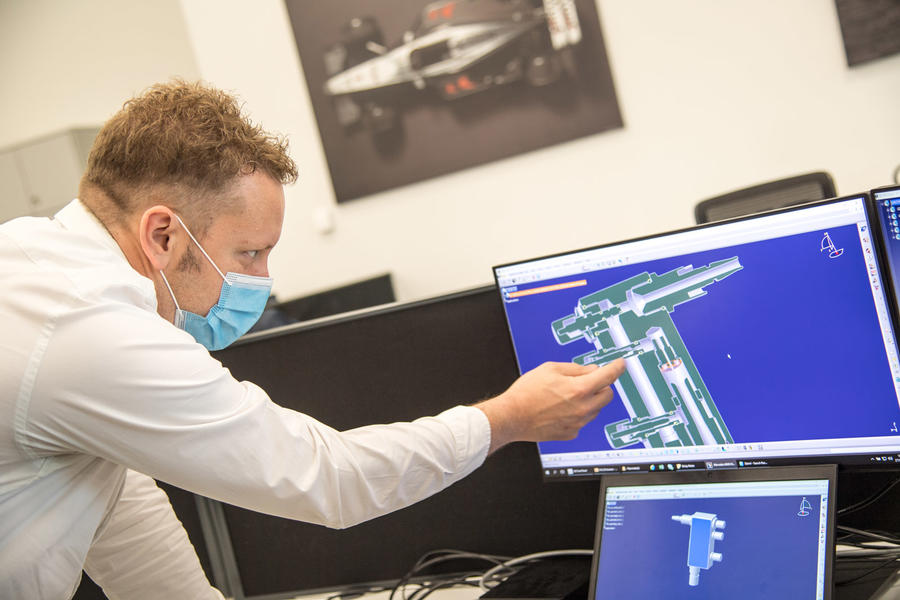

Mercedes-AMG – Ben Hodgkinson, head of mechanical engineering, Mercedes High Performance Powertrains

As head of mechanical engineering for Mercedes High Performance Powertrains, Ben Hodgkinson is used to pressure: he helps make the engines that have powered the Mercedes-AMG F1 team to seven straight drivers’ and constructors’ championships. But working on Lewis Hamilton’s engines pales to the challenge of reverse-engineering a small medical device.

“I’ve been in motorsport a long time, so I’ve never known any other pace,” he says. “It can be stressful, but I’ve managed it by saying ‘it’s not life or death’. But this actually was life or death. There was an intensity beyond anything I’ve experienced in F1.”

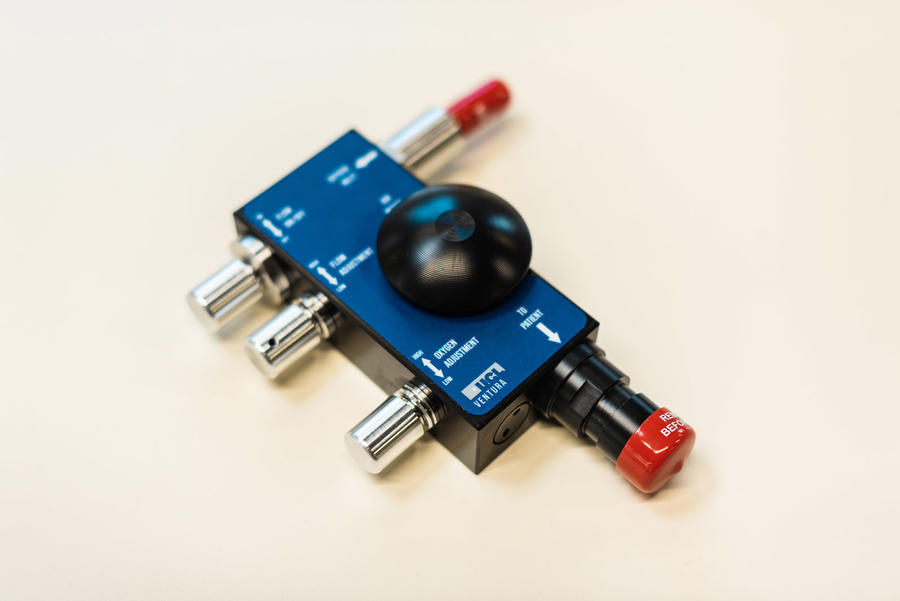

The WhisperFlow continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) unit is a mechanical device that enables consistent and effective oxygen delivery to a patient. Hodgkinson became involved in reworking it through his role as a guest lecturer at University College London, a position he was recruited to by Professor Tim Baker. The two had worked together at motorsport firms Mountune and AER.

“When Covid-19 was accelerating in March, Tim called to ask if I could help UCL Engineering work on some respiratory units,” says Hodgkinson. The government focus was on ventilators, but Professor Mervyn Singer and others at UCL Hospital weren’t convinced: their research, and the experience of colleagues in Italy, suggested less invasive CPAP devices could be a better solution. But most modern CPAPs required the same facilities as ventilators, so availability was limited.

“Mervyn found an old WhisperFlow in the UCL museum,” says Hodgkinson. “Tim asked if I could help reverse-engineer it.”

With permission from Andy Cowell, the then boss of Brixworth-based Mercedes HPP, Hodgkinson set off for UCL. “I was imagining a CPAP would be some massive old contraption with bellows and the like, and wondered ‘how can I invent one of those?’ But when I saw a little plastic block with valves in, I went: ‘Wow, that’s easy. We can do that. We can do that fast.’”

Hodgkinson sent photos of the WhisperFlow to Cowell, with a request to rope in some more engineers. “He agreed,” says Hodgkinson. “So three friends drove down to UCL with a lot of measurement kit from our lab.

“We worked through the night, stopped at 4am for three hours, then worked through until 4am again. By that time, we’d got all the modelling down and sent the first block back to Mercedes HPP. A team at the factory had already been looking at materials. Andy had found another WhisperFlow on eBay and the factory had started analysing it with the machines there. We did a full-on reverse-engineering job on it.”

The models and detail drawings went back to Mercedes, where close to 30 engineers were now involved. Within 36 hours of Baker’s call, Hodgkinson and Cowell delivered a working prototype of the new UCL Ventura CPAP to UCL Hospital.

“They were shocked at the level of detail we’d gone to,” laughs Hodgkinson. “We did mass spectrometry plots of the materials so we knew exactly what type of steel it was, that the rubber had fluorine atoms in and so on.”

Mercedes didn’t just replicate the WhisperFlow CPAP (its patent had expired in 2019). “We eventually collected four or five versions of the device,” says Hodgkinson. “On one, the oxygen fitting was glued in with epoxy resin where it had broken, so we knew that was a design flaw. We replaced them with hydraulic fittings. We fixed all the issues.”

Mercedes improved more than the CPAP itself. One issue is how intensively they use oxygen, so the team undertook further CFD analysis on air flow, leading to modifications to boost efficiency. The improved UCL Ventura Mk2 followed five days later.

By that stage, the NHS had issued new guidance on the use of CPAP devices to treat Covid-19, and the government ordered 10,000 – produced by Mercedes in a fortnight. That meant UCL and Mercedes could cover their costs, which wasn’t guaranteed at first. “Andy and Mercedes HPP were brilliant about it,” says Hodgkinson. “They didn’t want to make any money. It was about doing the right thing.”

Hodgkinson contracted Covid-19 as the second clinical trial was done, and was “quite ill” for two weeks. But it was worth it. The UCL Ventura is now in use in 110 NHS hospitals and its designs are available on a non-profit basis. So far 1900 licences have been issued across 105 countries.

“It’s amazing how many people have downloaded our plans,” says Hodgkinson. “There’s a lot of banter in our office, with people saying ‘it’s not rocket science’, that this was just a simple plastic block. Then one day NASA downloaded our design, and we just went ‘ah, apparently it is rocket science’…”

Vauxhall – Thomas King, supervisor, Vauxhall Luton

There’s a big difference between a Vivaro van and a medical ventilator, so as much as Vauxhall wanted to help production efforts to meet NHS demands, there was no question of converting the production line at its Luton plant. A short distance away, however, medical manufacturing firm Smiths Medical was working out how it could increase production to deliver an order for 10,000 of its well-established ventilators – in just four months.

To help, Vauxhall bosses called for volunteers from its furloughed workforce to work on the Smiths Medical production line.

“About 15 of us volunteered,” says supervisor Thomas King. “It was daunting initially, coming out of our homes every morning with masks, hand sanitiser, gloves, a bottle of bleach and a letter in case we were stopped by authorities for being out.” He says the team was immediately welcomed by Smiths, with “the realisation that all the suffering was bringing us together”.

So how easy was the shift from making vans to ventilators? “Given our experience of building and assembling vans, I was confident we could adjust, but that wasn’t the case,” says King. “The main challenge was the size of the parts that needed to be sub-assembled: many can only be seen with a magnifying glass.”

Still, once they’d got their eye in, the Vauxhall employees were able to offer some tips. “We could contribute our experience of working in a rapid production environment,” says King. “We introduced a lot of ideas on lean production, which helped with the need to increase output from five per week to 35 per day. And we’ve been able to take back to Vauxhall the experience of building a sophisticated medical device – and the experience of a wartime effort with an unknown group of people is something that will stay with them for a lifetime.”

King says the camaraderie between the Vauxhall and Smiths teams has continued. “Plans are being put in place to celebrate the success we shared when Covid finally passes,” he says. Until then, King praised the Vauxhall team for being “completely selfless in the sacrifice they made”. He adds: “It’s certainly a memory I will carry with me for my lifetime. I don’t think I’m alone in saying that if given the chance, I’d do it all over again.”

Ford – Martin Everitt, Dagenham plant manager

With concerns about the availability of NHS ventilators in March, the government called for manufacturing firms who could rapidly develop and produce them at scale. In response, a group of medical, aerospace, technology, F1 and automotive firms formed Ventilator Challenge UK, with a plan to mass-produce two existing ventilator designs.

Ford was tasked with making subassemblies at its Dagenham plant, and the job of working out how to do it fell to plant manager Martin Everitt. “We were excited, but it was a challenge,” he says. “You can’t just make ventilator parts on an engine production line.”

Everitt decided to use Dagenham’s vacant J building. In three weeks, they laid out and installed 200 socially distanced work stations to construct parts they had never made before.

“We’ve never assembled a similar facility in anywhere close to that timescale,” he says. “We didn’t wait until everything was 100%: we were doing manufacturing development on parts as we were putting equipment on the shop floor.”

The facility was initially staffed by engine plant workers on furlough ( “a great way of using the skills we’ve developed”), but ventilator component production was ongoing when engine manufacturing was due to resume post-lockdown. So Everitt recruited local agency staff, in part to help the community. “We hired people who had fallen through the cracks of government support,” he says. “We had taxi drivers, plumbers, musicians and an airline pilot.”

Training a disparate range of staff with limited time and under social distancing rules was a challenge, so digital training tools were used. “We had a project expert who had to self-isolate, so we used a HoloLens [Microsoft-developed ‘mixed reality’ smart glasses] so he could do realtime diagnosis of problems,” says Everitt. “We’re now planning to use it in engine production: it can help us fix issues in real time.”

Production ended in July, with Ford having helped to produce 13,437 ventilators in 12 weeks. “There’s a huge sense of pride from the whole team,” says Everitt, “both in helping the country and showing how good UK PLC is at manufacturing.”

Aston Martin – Connor O’Toole, interior trim development engineer

In the early days of the pandemic, Aston Martin’s trim workshop started a staff rotation, with employees working from home every other week. It was while working at home that Connor O’Toole admits he began to feel guilty. “So many brave NHS workers, including some of my family, were out battling this unknown virus and risking their lives,” he says.

On learning of the dramatic shortage in PPE, O’Toole talked to his boss about helping out, by making clothing for the NHS. Aston Martin management contacted two local hospitals and discovered they were in desperate need of medical gowns and scrubs.

“We asked the manufacturing team for volunteer sewers and machine operators,” says O’Toole. “It meant bringing people back from furlough to support this effort in the height of the pandemic – and in glorious summer weather.” About 30 staff volunteered. Specialist sewing machines were obtained from supplier Rob Small, and within a week the department was ready to start manufacturing.

O’Toole made patterns in various sizes based on sample scrubs and gowns provided by the hospitals – “with some small modifications to speed up manufacturing” – which were then digitised for use on Aston’s machines. The hardest task was sourcing medical-grade waterproof material, so an Aston Martin director went touring the country – in a new DBX – in a bid to find some.

Over a 12-week period, Aston’s volunteers produced 2800 scrubs and 2100 gowns. Following early requests, they even added special Aston Martin labels featuring the winged badge. “We actually had a doctor from another hospital putting in an order because he wanted his whole team kitted out with Aston Martin attire to boost their mood,” says O’Toole.

While he admits that organising the production was stressful, O’Toole says it was “worth it all seeing what we achieved working as a team”. But he says the best part was supporting the NHS staff. “They deserved to be safe when they did the most fantastic job for the country,” he says.

Bentley – Lawrence Jones, head of health and safety

Like many people, Lawrence Jones has spent much of his year dealing with issues he had never previously considered. As Bentley’s head of health and safety, that has spanned everything from how to build cars safely to the seemingly trivial. The oddest? “I never thought I’d have to work out how to implement social distancing at a urinal,” he says.

Covid-safe toilets might seem minor, but in the context of a car factory, it’s a real problem. If social distancing measures slow the flow of workers who need to, er, let flow, then that risks disrupting the flow of Flying Spurs off the production line.

In case you were wondering, having initially taped off every other urinal, Jones and his team installed Perspex shielding between each one to restore full capacity. Like much this year, such issues would have been unthinkable before Covid-19. “If a year ago someone said ‘this is where you’ll be at the end of 2020’, I’d have thought they were mad,” says Jones.

Jones first began to sense the world was about to change beyond recognition in January, when China’s lockdown caused several Volkswagen Group plants in the country to close. By February, Bentley’s crisis management team was meeting once a week; little more than a month later, as Covid-19 reached the UK, those meetings were daily.

“We were obviously worried about the potential impact on the business, but the real focus was on our people,” says Jones, who is responsible for ensuring the 3500-plus workers at the factory are safe.

While the UK lockdown forced the factory to shut, there were still around 250 people on site every day to perform essential activities. And while keeping them as safe as possible from a novel virus, Jones was already trying to work out how to reopen the factory.

Being part of the VW Group helped: Jones drew on experience from reopening the group’s plants in China and elsewhere, helping him formulate a plan of safety measures that were used as the basis for a Covid-19 risk assessment. The challenge was putting that theory into practice, which involved the installation of many of the oh-so-2020 measures you’d expect.

“We made around 300 physical changes across the site, including signage, one-way systems and physical barriers,” says Jones. “It was all aimed at making sure people felt confident coming back and that they were safe. Typically, a lot of activities in the car industry involve working side by side, so we started back at a slower pace so people could get used to the systems.”

Perspex barriers weren’t just used in the toilets: they have enabled engineers to work closely together on production lines and to sit closer at tables in the staff canteen. Every staff member was given a bottle of hand sanitiser, with refill stations placed around the factory. Kick-pulls were installed on doors so they could be opened hands-free, and masks, provided by Bentley, were required on site before the government made them compulsory.

Then there was the challenge of introducing a Covid-safe, socially distanced one-way system in a factory not really designed for it. “It’s easy to do a desktop risk assessment, but the most effective way is to go out and actually look at the risks and hazards,” says Jones. “We had areas where if we made a corridor one-way in one direction, we blocked access to something else. We had a plan of the site, and involved the safety and security team and union reps. We then walked the site – we even got [CEO] Adrian Hallmark involved – to work out the best system.”

While making the site safe as the phased reopening began, Jones also introduced privately sourced employee testing. More than 7400 tests have been administered, from a temporary site established just outside the main factory. “We felt a responsibility to our colleagues, their families and the local community,” he says. “We don’t want anything coming into Bentley, spreading here and then going out.

“We also identified higher-risk groups within and outside the business: around 280 of our workers live with a first-line care-giver, so we test those colleagues every week for Covid-19 to help protect the NHS.”

The firm is also paying for flu vaccines for all staff who want one and has established its own test and trace system. Any employee who feels unwell off-site is told to stay away and source their own test; anyone who feels unwell while on site is isolated and tested. “Does that cause us problems from a production point of view? Yes, but we aren’t compromising on isolation,” Jones says. “If people are told to isolate, they isolate. At times we’ve had to slow down and look for additional resources. We’ve brought people back into engineering, and we’ve upskilled apprentices to help fill the gaps.”

Bentley has also trained 40 new mental health first-aiders, and has so far conducted more than 8000 occupational health screenings. So far there is only one suspected case of employee-to-employee transmission. Jones is quick to praise others – from Bentley’s directors to its employees – for the success of the provisions he’s introduced, noting it has been a true team effort. “It’s proven how good any business can be if we collaborate,” he says. “That’s my key takeaway from this.”

How the wider industry helped

Here’s just a sample of the other ways car firms have mucked in during the coronavirus crisis

Envisage: The coachbuild and concept vehicle specialist produced a new portable ventilator made from off-the-shelf medical parts to help the UK government combat Covid-19.

Jaguar Land Rover: Lent 160 cars, including 27 new Defenders, to groups including the Red Cross and the NHS. Produced NHS visors at a rate of around 14,000 a week. Also made the design files open source, thus allowing other firms to freely produce the visors.

MG Motor UK: Supplied up to 100 ZS electric SUVs to NHS agencies free of charge for six months and donated 30,000 face masks to UK and Irish hospitals.

Nissan UK: Helped to increase production and distribution of 3D-printed PPE supporting an effort started by employees Anthony and Chris Grilli. Also offered free roadside assistance to NHS and key workers who drive any of its vehicles and worked with dealers to loan demonstration and courtesy cars to NHS workers for free.

PSA UK: PSA Group brands Citroën, DS, Peugeot and Vauxhall offered free roadside assistance to NHS workers who drive their cars and vans and increased goodwill payments to NHS workers whose vehicles were no longer within warranty. They also donated more than 50,000 protective face masks to the NHS.

Rolls-Royce: Produced face visors at its Goodwood factory for local NHS staff. Also released a fleet of 30 cars to local charities and NHS services.

Skoda UK: Supplied modified Karoqs, Kodiaqs, Superbs and Octavias to emergency services and front-line care providers, including NHS trusts.

Toyota and Lexus UK: In partnership with the AA, gave free roadside assistance to key workers who drive their cars and vans.

Williams Advanced Engineering: In response to the Ventilator Challenge UK project, the Williams F1 team’s engineering offshoot worked with firms including McLaren and Rolls-Royce to re-engineer the Smiths Group ParaPac 300 ventilator so that 5000 units could be produced rapidly for the NHS.

Around the world: It wasn’t just in the UK that car firms offered their services. That dated from the early days of the pandemic: by April, Chinese car maker BYD had assembled a factory producing five million face masks and 300,000 bottles of disinfectant per day.

Elsewhere, Volkswagen paid German employees who volunteered to work in the country’s health service and paid to import medical equipment from China.

Ferrari produced respirators and masks at Maranello and partnered the Italian Institute of Technology to develop a ventilator.

Seat also produced ventilators at its Martorell factory near Barcelona.

Ford and General Motors answered US government calls to produce similar units; Ford’s efforts included working with 3M to make powered air-purifying respirators using parts repurposed from its F-150 pick-up.

The PSA Group was part of a consortium that produced 10,000 ventilators for France’s government.

READ MORE

Zoom meeting: The Autocar road tester’s Christmas lunch

Source: Autocar