Dry clutches and a lack of computing power meant early DCTs were rough

Why do we hanker after manual gearboxes when dual-clutchers have huge all-round benefits?

Four decades ago, a technology that would eventually have a massive impact on the drivability of cars today was born. The dual-clutch transmission (DCT), now a common feature in most cars to the point of exclusivity in some, was dreamed up by a small team of engineers at Porsche who by their own admission were probably punching above their weight at the time.

The Porsche Doppelkupplungsgetriebe (PDK transmission) almost proved a bridge too far in the early 1980s. Computing power was a fraction of what it is today, yet the engineers managed to make it work well enough to gain big advantages in Group C racing with the Porsche 962 and in rallying with the Audi Quattro S1. So now, when the technology has not only been perfected but evolved into something far better than ever could originally have been imagined, do drivers clamour for a return to stick-shifts?

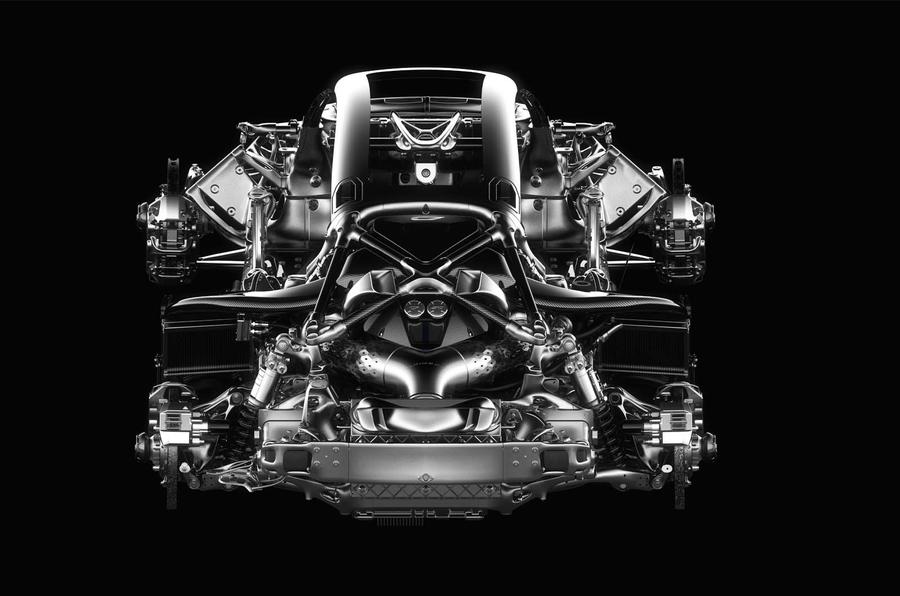

The idea of the DCT is that theoretically it should be possible to swap ratios with no interruption of torque in just a few milliseconds. By having the forward speeds of the gearbox split between two separate clutches, each forward speed can be preselected and the ratio changed by simultaneous opening and closing of the clutches, taking one ratio out of the equation and bringing the other into play. The shift is made not by physically selecting each gear as it’s needed but by the opening and closing of the clutches.

In those early days, the lack of processing speed meant the shifting was rough. The inability to perfectly synchronise the clutches resulted in vicious jumps forward when the shift was made, placing heavy strain on the driveline at the same time. The refinement and robustness wasn’t there to satisfy the needs of everyday road cars.

Twenty years on, high-speed processing and the development of motorcycle-style wet-clutch technology (clutches bathed in oil rather than running dry in air) finally made the DCT a perfect production reality.

So if that’s the case, why do so many of us hanker after a manual gearbox, in some cases forcing its reintroduction to cars from which one had been deleted?

It may be down to psychology. The average time to shift smoothly with an H-pattern ’box is probably around half a second vertically and much longer than that when moving across the gate. During the DCT’s transition period from motorsport, along came single-clutch automated manuals, like Alfa Romeo’s Selespeed and BMW’s SMG. Both were criticised for slowness compared with a manual, despite figures to the contrary. One engineer attributed this discord to perception, because the driver had nothing to do while the shift was being made. That may well have been the case and is probably also why indisputably faster DCTs remain unpopular with some keen drivers.

However clever, they lack the involvement of a manual and the challenge of producing a well-co-ordinated shift. It’s that driver involvement and sheer pleasure of getting the absolute best out of a machine that, ironically, automation can never replace.

Print off your next car

The Czinger 21C hypercar owes a significant amount of its production to 3D printing, so how long will it be before cars can be 3D-printed in their entirety? The jury is still out on that, although the greater simplicity of electric drivetrains should help. Research firm Hubs predicts that the value of the 3D printing market in general will increase by 24% to around £38 billion by 2026.

Source: Autocar