Ford CEO Jim Farley expects the Inflation Reduction Act will help its profitability “quite a bit”

Moves to protect against China’s battery dominance throw the freedom of the car trade into doubt

The canary in the coal mine was struggling EV start-up Arrival, which said in October it was shifting its production focus from the UK to the US to take advantage of the country’s generous new subsidy package.

Arrival’s statement was blunt. “The major factors in the company’s decision to shift focus to developing its US business included the tax credit recently announced as part of the Inflation Reduction Act – expected to offer between $7,500 (£6300) to $40,000 (£33,000) for commercial vehicles.”

The cash-starved start-up might very well have to shut its doors before taking advantage of those subsidies but the fact that it was willing to up sticks when it was so close to starting UK production shows what a profound effect the US’s subsidy programme is having.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was signed into law in August as a blockbuster $369 billion (£307.6bn) subsidy package focusing on low-carbon technologies, including electric cars, but crucially only available to those who build on US soil.

Countries across the globe have a long history of protecting their own industry by granting favours not available to those building outside its borders. However, in recent years, globalism has been the engine of growth as world’s biggest car markets lowered barriers, leading to more vehicles being shipped across the world.

Consumers have benefited accordingly. The advantage of lowering tariffs and other non-tariff barriers to foreign cars is that it forces your own industry to raise its game and become globally competitive. The disadvantage is that it might allow foreign players to grab sizeable market share by outcompeting in a key area such as quality (as seen on the first Japanese vehicle imports). The danger there is that your own industry might slide into irrelevance before it can react; witness the UK motorbike industry in the 1970s.

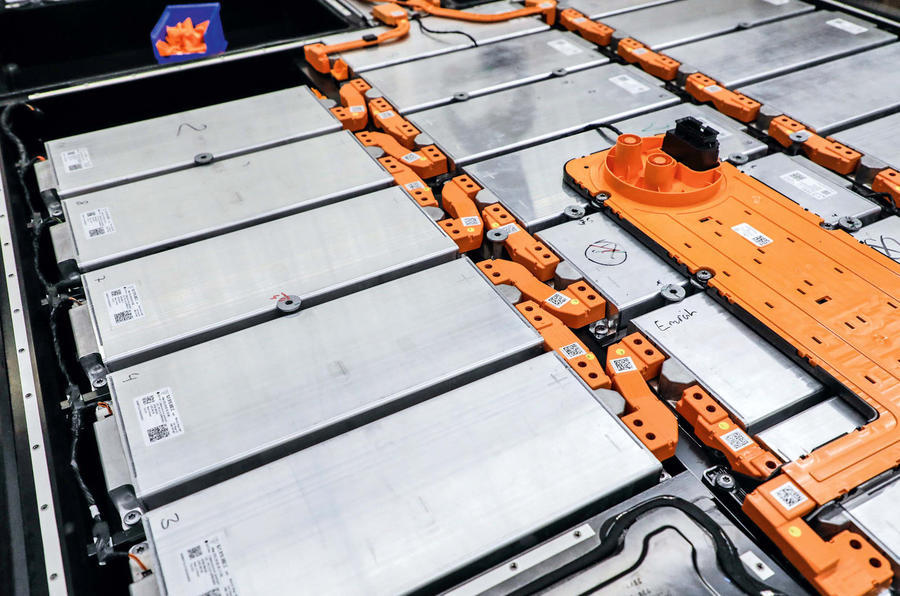

The IRA subsidy scheme brings the whole globalism trend to a screeching halt. The country in part was reacting to the seemingly unstoppable rise of China and its iron grip on battery chemistry, something it has been working on for some time with copious state support. China controls 70% of the world’s battery cathode production and 80% of its anode production and makes 75% of all battery cells, according to data from the International Energy Agency.

Even if you wanted to wrest control of that production, it’s likely that China has got there first.

“China controls the metals that are vital to the modern economy,” Simon Moores, CEO of London-based battery materials consultant Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, wrote on Twitter.

What the IRA does is try to halt that advantage by doling out subsidies up to $7500 (£6243) for the purchase of electric and plug-in hybrid cars in which the batteries pass minimum local content requirements; with materials mined or at least refined in the US.

They will get tougher year by year, so starting from 2023 the ‘critical minerals’ requirement is 40% of the value of the battery, rising to 80% from 2027. The same applies to the percentage of the battery that is assembled in the US, rising from 50% in 2023 to 100% after 2029.

There are other subsidies – those for commercials, as mentioned, go even higher. The government’s Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing (ATVM) Direct Loan Program has lifted its cap of $25bn (£20.8bn) to provide funding for companies looking to build out their manufacturing capabilities in the right, low-carbon direction. And there’s also a tax credit available to battery manufacturers.

As you can imagine, automotive companies in the US are pleased with the incentives.

“We expect the Inflation Reduction Act to have a wide range of positive impacts for both our customers and for Ford,” Ford CEO Jim Farley said on the company’s third quarter earnings call.

![]()

Farley cited the battery-production tax credit as having the biggest potential impact, which he calculated as being worth about $45 (£37.46) per kWh for Ford and its battery partner SK On. Given the world’s cheapest EV battery right now – made by China’s CATL – costs an estimated $134/kWh (£111.60), that’s huge.

He also cited the commercial EV credit, the loan facility and the car purchase subsidy; the latter available for the Mustang Mach-E electric SUV (pictured above) and the F-150 Lightning pick-up truck.

“I think this will have a dramatic impact on the adoption of EV,” he said. “This will help our profitability quite a bit, even next year.”

At a recent investor conference, General Motors indicated that IRA subsidies could add between five and seven percentage points to its profit margin and make up “more than half the margin dilution from EVs”, reported Philippe Houchois, lead automotive analyst at the bank Jefferies.

Of course, this has infuriated European carmakers. Regional lobby group ACEA spoke of its “disappointment” at the incentives. “The scope of the incentives for electric vehicles needs to be far more inclusive in order to achieve the rate of positive environmental change that our sector is committed to,” it said in a statement. Any EV incentive scheme should instead “be applied in a fair and equitable manner”, it went on.

Car makers much bigger than Arrival are looking hard at their production plans. For example, the IRA “will have a huge impact on our strategy [in North America]”, Oliver Hoffmann, the head of technical development for Audi, told Automotive News. “We will look where we want to produce our cars in the future.”

The only Volkswagen Group EV that might currently qualify is the Volkswagen ID 4 (pictured below), made in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Meanwhile, VW battery partner Northvolt said in late November it could delay plans to build a factory in Heide, northern Germany, as it re-evaluates plans in light of the generous US subsidies, Bloomberg reported.

The anger at the US move has hit the top levels of European governance. A recent joint statement by the French finance minister, Bruno Le Maire, and his counterpart in Germany, Robert Habeck, called for a similar scheme. “We want to coordinate closely a European approach to challenges such as the United States Inflation Reduction Act,” it read.

They announced a working group to accelerate co-operating on hydrogen technologies as well as expansion of the Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI), which has been pouring money into localising the battery value chain.

China has been pushing its own form of protectionism, with measures including the application of relatively high tariffs of 15% for vehicles imported into the country.

Those European car makers without substantial local Chinese production interests to protect have been vocal that Europe raises its tariffs from the current 10% to level the playing field.

“We should ask the European Union to enforce the same conditions in Europe for Chinese manufacturers under which we, the western manufacturers, compete in China,” Stellantis CEO Tavares told journalists at the recent Paris motor show, where Chinese car makers like BYD and Great Wall were conspicuous.

China’s strength in batteries is starting to make itself felt in Europe. Through August, almost a fifth of all electric cars registered in Europe were Chinese built, Jato Dynamics reported, with only Germany building more for the region.

That Chinese battery cost advantage can be seen in the new MG 4 EV, which starts at £25,995, compared with £36,990 for an almost comparable VW ID 3, thanks in part to the cheaper battery chemistry from supplier CATL.

When the world’s biggest markets are putting up barriers, Europe should follow, French president Emmanuel Macron told Les Echos paper in October: “The Americans are buying American and pursuing a very aggressive strategy of state aid. The Chinese are closing their market. We can’t be the only area, the most virtuous in terms of climate, which considers that there’s no European preference.”

The EU is so concerned that it has set up a taskforce to discuss with Washington to avoid tit-for-tat tariff increases.

Liesje Schreinemacher, the Dutch trade minister, was quoted by the Financial Times last week as saying the IRA was “very worrisome”. She said: “I want to avoid a trade war by any means. No one benefits from any trade war.”

The EU does have a couple of non-tariff barriers to fight back with. One was delivered as a result of Brexit, which is ironic, given that Brexit was partly fought on the ideal of barrierless trade everywhere. The trade agreement that the UK signed with the EU mandates levels of local content in regionally-built cars, rising year by year. For example, 45% of the content of electrified vehicles built in the UK or EU has to be sourced there, rising to 55% by 2027.

The other potential blocker – to Chinese battery content in particular – is the EU’s revised battery directive, adopted by the European Council this year and expected to be passed by the parliament soon. This forces a number of conditions on the batteries used in vehicles and other devices from 2023, including requiring labels indicating the battery’s carbon footprint, which might end up favouring local production. However, this isn’t its stated aim.

Some car makers think the US has gone too far with the scheme, even as they stand to gain. Ford, Stellantis and VW are pushing for increased Chinese content in batteries amid concerns that China has too great a control of the minerals market to fully source elsewhere, the Financial Times reported. Ford announced in September it would be sourcing batteries from China’s CATL from 2023 for both the Mustang Mach-E and the F-150 Lightning.

Ending two decades or more of cost-reducing global sourcing is not going to be easy.

What impact will the Inflation Reduction Act have on the UK?

Arrival’s announcement is the most vocal reaction to the US scheme, if not one that will have a massive impact on UK automotive. However, the US move does heap one more threat on an already beleaguered industry.

The UK industry’s lobby group, the SMMT, has called for the government to protect the UK industry from global threats like the IRA subsidy. “We face fierce global competition and in the global race to net-zero we must be as attractive – more attractive – than rival countries against whom we will compete for investment,” Alison Jones, Stellantis’s head of circular economy, told attendees of the SMMT dinner in London on Tuesday.

The group stopped short of asking for subsidies to favour UK-built electric cars, but we would struggle to launch our own version, because we build too few electric cars and the EU could all too easily retaliate with tariffs if it felt shut out of a scheme that favoured UK cars.

Given that the UK exports the bulk of the cars it makes, it prefers to push for lower tariffs rather than impose them, given that it would lose more than it would gain in the event of a trade war. Witness our free trade deal with Japan signed in 2020, which reduces import tariffs for Japanese-made cars to zero by 2026.

So would the IRA have an impact on cars we export to the US? Right now, we send over only a handful of EVs and plug-in hybrids, so the effect might be marginal. The maximum price for electrified vehicles that qualify for the credits is $55,000 (£45,834) for standard cars and $80,000 (£66,668) for SUVs. The majority of US-competition for the likes of the Jaguar I-Pace and future electric Range Rovers will be above that – although it could reduce the price of rival Cadillacs and Lincolns below the threshold.

The danger comes if a company such as Nissan or Toyota decides that the production incentives are appealing enough to make the US its export base for electric cars to Europe, instead of Sunderland or Burnaston. This has already happened with BMW and Mini, which decided that China held too great a production advantage for EVs so it will build its next Mini EV there, instead of Oxford.

If we do finally nail a free trade agreement with the US with the subsequent removal of tariffs, that could be a real concern. Our free-trade deal with Japan could also swing the pendulum the other way too, making Japanese factories look more appealing as an export base (something that already happened with the incoming Nissan X-Trail hybrid, which Sunderland lost to Japan).

Source: Autocar