Richard Webber and Max Edleston met at Port Edgar just outside Edinburgh

We take the Swedish brand’s all-electric saloon to Shetland exploring wild nature… and ferry crossings

“This isn’t quite the end of the earth – but you can see it from here,” quips one of our hosts. Looking north from our windswept perch across the heaving seas, I think he might be right. We’re closer to the Arctic Circle than we are to London, but our passports are safely at home because we’re still in the UK. Just.

Rewind 24 hours and Autocar staff photographer Max Edleston and I meet at Port Edgar, a smart marina just outside Edinburgh, with a plan to drive north until the blacktop stops. Our car for the journey is a fully electric Polestar 2, whose namesake celestial body – variously known as the Pole Star, Polaris or the North Star – will guide us there, hanging as it does directly above the North Pole.

![]()

We’re in the entry-level 2, which means 228bhp, front-wheel drive and a claimed range of 297 miles. Limited to 100mph, it’s a pragmatic spec for a relatively pragmatic car. As such, the 2 isn’t overburdened with modes and I’ve already found ‘mine’ – the middle choices for regen (intended to mimic engine braking) and for steering (it’s overly light or overly springy otherwise), with step-off creep switched on.

Queensferry Crossing’s cables gleam white in the sunshine as we silently span the Firth of Forth, the Polestar’s easy-going character immediately apparent. There is a slight bobbing over the M90’s smaller ripples as we press through Fife, otherwise it’s how exactly motorway driving in an electric car should be: clean and serene.

If we’d been heading for John O’Groats, we’d keep our course at Perth, but we have bigger plans. We veer coastwards past Dundee and on to Aberdeen, the gateway to Britain’s most distant outpost: the 100-island archipelago of Shetland.

We’re hoping to drive the length of Shetland and back without needing a charge, so after an untaxing cruise we pause at Porsche Centre Aberdeen to use its public DC rapid charger, meaning the battery is at 99% as we turn into the NorthLink Ferries terminal. (There are AC fast chargers at the port, but you can’t charge on board – the logic being that using the ferry’s four diesel engines as generators for EVs would be self-defeating.)

We soon board the imposing, 125-metre MV Hrossey. This route is vital to industry, commerce and leisure alike and the ship can take 600 people and 140 cars. The Polestar installed on the lower of two vehicle decks and ourselves in a pair of compact but impeccably equipped cabins, we’re under way by the time we sit for dinner.

In keeping with every Scottish island ferry I’ve been on, there’s a noticeably cheerful atmosphere on board. Something to do with all being in the same boat, I suppose.

A postprandial recce to the deserted top deck has me peering into the now pitch-black sky. Jupiter blazes to the south-east, but cloud scotches the view north. A stargazing app confirms the Pole Star’s location, though, reassuringly plumb between Hrossey’s funnels.

Something about the North Sea’s (thankfully gentle) sway through the night means my subconscious has logged we are somewhere very different by the time we disembark in Lerwick, unlike the shock of arrival following a long flight. It’s just before 8am as we slip through the town’s ancient streets, stopping to photograph the Polestar between two of Lerwick’s characteristic Georgian-era lodberries – saltlicked, rubble-walled stores founded in the sea. The car’s sleek modernism provides a bracing contrast.

We’re on Mainland, the largest of the Shetland Islands group, but our goal means heading for the second-largest. Therefore, to reference Chris Rea’s other famous song about driving, we find ourselves continuing further north still, on the Road to Yell.

The sweeping A970 is surrounded by chocolate-brown moorland, lochans and absolutely no trees. But energy sources abound here. The moorland is mainly peat: once the primary fossil fuel used on Shetland. Now, the bulk of its electricity comes from the diesel-fired Lerwick Power Station and a gas-fired station at Sullom Voe, where crude oil and gas extracted from around the North Sea and Atlantic Margin is shipped and piped in for processing.

Yet renewables are on the rise. We pass the entrance to the enormous Viking Wind Farm, whose 103 4.3MW turbines – each a towering 155m high – are currently under construction and will have the capacity to power almost half a million homes – which is one reason a high-voltage cable to the UK mainland is also being laid, allowing Shetland to share energy for the first time.

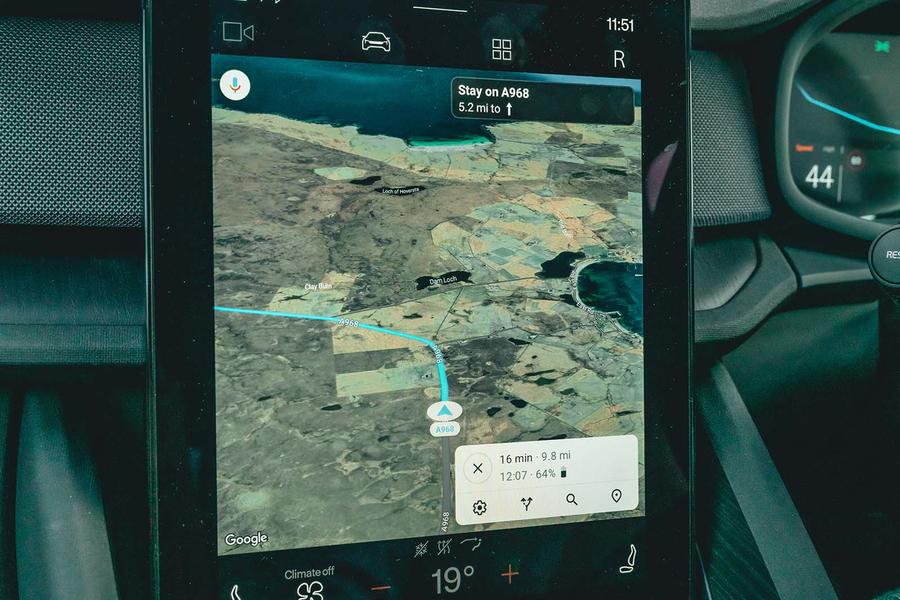

We’re busy managing our own power needs in the Polestar. The infotainment’s excellent Google Maps app (integrated with battery status to help manage charging stops) says we’re cutting it fine for the Yell ferry, so we pick up the pace while keeping inputs smooth, which suits the 2 nicely. This may be the less powerful, 228bhp model, but in the real word it feels quicker than its two-tonne kerb weight and 7.0sec 0-60mph time imply, particularly with the absence of gears to shuffle.

In fact, it feels rather like a teetotal hot hatch. There’s minimal roll along the flowing esses high above the rain-specked waters of Swinister Voe, and the steering, while typically stolid, is faithful and responsive without being edgy. Power is laid down with impressive composure: on all but sodden patches it sticks like Weetabix to a toddler’s face, and any torque steer is limited to a distant stiffening of the wheel. You needn’t dwell on this being a front-drive car.

We spot one of the Sullom Voe’s flare stacks burning orange on the horizon before banking off to the ferry terminal at Toft, where the MV Daggri – half the length of Hrossey – awaits us for the 20-minute crossing of Yell Sound.

Halfway over, it passes its twin vessel: the pair tag-team opposing routes all day long. We perch on the observation deck to watch shallow islets drift by beneath a sky that’s blue, white, grey and yellow all at once. It’s a tonic to the daily grind; I can almost feel the cortisol draining away.

Yell is noticeably quieter than Mainland and is a wildlife paradise. We barely pass another car; the only hold-up comes from a pair of rams literally battering each other in the middle of the road. And what a road – smooth, fast and flowing. Despite this, I’m not yearning for a searing, tuneful atmo engine, because the pervading peace of electric drive and the Polestar’s undemanding mien are letting our senses focus on the almost cinematically lit scenes we’re passing through, from the bizarre double tombolo at Ness of Sound to the ragged ginger bogland that fringes Whale Firth. At the top of Yell we peel onto a single-track road that runs alongside Bluemull Sound. At one point we have to reverse into a passing place, but while the rearward view is quite stingy, between the optional 360deg cameras and chunky, fussfree shifter, it’s a cinch.

A couple of miles on, we turn onto the commercial pier at Cullivoe. We pause to meet a greedy and extremely round Shetland pony before seeking out the most novel of charging points, tucked away in a corner. Unveiled last year, it’s free to use, and we top the battery up in the certain knowledge that no fossil fuels are being burned in our name, because it is powered entirely by the tide. Just 800m away, four tidal turbines from Nova Innovation are weighted to the seabed and sending energy to our car, and indeed the local grid. Using it feels somewhat validating.

We double back three miles to Gutcher ferry terminal, where we have one more crossing still to make. It’s a pretty little spot, with short piers and a dirt-track tombolo, made no less quaint by the curious otter (‘draatsi’ in the local dialect) that frolics by. Orcas are also frequent visitors but, thankfully for the otter, not today.

The Russian-doll sequence of ferries continues as the MV Bigga – half the length of Daggri – seemingly handbrakes into port, mouth agape. It’s a clockwork operation: arrival, unloading, loading and departure all takes no more than 10 minutes. Once under way, we ride the swell, surreally taking in the rocking horizon and sound of the sea from the 2’s sober but comfortable cabin.

In a heartbeat, we arrive on Unst, perhaps the most spectacular among these spectacular islands, and our final destination. On the quayside towers a pair of bright yellow tripods of Teesside steel – substructures for two more tidal turbines that will soon be added to the array, when their nacelles will be mounted on top.

There are only 14 miles of road left as we point north one last time. We’re on 69% charge so can afford to spend more reserves on adding climate control to the seat and (optional) steering wheel heating with which we’ve made do so far. Still, the touchscreen range assistant says we’re actually accumulating around 0.2kWh for every mile we spend going downhill.

Much of Unst is fertile farmland, with fenced or stone-dyked green fields rather than uncontained peat moors. There is also a higher density of rural Viking sites than in even Scandinavia itself. Other attractions are less ancient, such as Bobby’s Bus Shelter, redecorated annually by locals and currently still sporting royal froufrou for the Platinum Jubilee.

The ground rises as we near the end of the island and we spot the radar dome of RAF Saxa Vord nestled on its highest point. A Cold War station built to scan from Iceland to Norway, it was recommissioned in 2018 to track increased Russian aircraft activity around UK airspace.

The two-lane road runs out just after the replica Norse longhouse and ship at Haroldswick, where we turn north-east as far as the hamlet of Norwick. It’s wild country, here – we’d have taken Skaw Road next, but for the inconvenience that it slipped into the sea some years ago. Instead, we follow Holsens Road, which takes us up and along the clifftop, becoming very narrow and coarse, with clumps of turf crowning its camber. This is it: the most northerly of the UK road network’s 247,800 miles.

It tracks downhill again, then a gentle right-hander reveals a farmstead next to a beautiful bay called Wick of Skaw. Asphalt gives way to gravel, then grass, a stream, a sandy, fawn-coloured beach and finally the crashing waves of the North Sea. It’s a rather perfect terminus.

Until its owners return from their stroll, there is one other car here – a Ford B-Max that is both unlocked and missing its front passenger door handle. This is symptomatic of two facts about Shetland: that, notwithstanding the eponymous BBC police drama, it has the second-lowest crime rate in the UK (Orkney is first), and that beyond Mainland, cars don’t need an MOT to drive here.

We wander onto the beach to absorb the tranquillity. There is not another soul. Of course, the CO2 debate is far more complex than tailpipe emissions alone, but we’ve driven here without producing any and seen how wind and even tidal energy can power such trips. The Polestar has been a usefully and enjoyably easy-going partner: a complex machine made uncomplicated to use. But this story has an epilogue.

While we have followed the Pole Star as far as we can, a glance to the right reveals the starting point for an entirely different celestial journey. On a jagged granite peninsula, we can just make out a gang of heavy construction vehicles. It is SaxaVord spaceport, which next spring is planned to host the first vertical rocket launch to orbit from UK soil. With a payload of satellites, rockets from around the globe will hurl heavenwards across a 60deg sector centred directly on the North Pole.

We’ve been given the nod for a closer look, so backtrack for five minutes before taking to the muddy construction road that snakes one and a half miles to the end of Lamba Ness. Until ground broke in February, the headland was home only to some derelict buildings, the broken stumps of wooden masts and a couple of craters courtesy of the Luftwaffe: the remains of World War II radar station RAF Skaw.

Today, concrete-pouring has just begun on the first of three launchpads. The site will also host hangars for rocket assembly and sterile satellite preparation. Rockets around 30m high – some will return, others won’t – will usually run on a mix of liquid oxygen and RP-1 rocket fuel. The spaceport is privately funded and will let time on its facilities to rocket operators.

It’s a huge project, but there are of course sustainability considerations. The spaceport is investigating the possibility of energy self-sufficiency using renewable sources, and measures are in action not to displace local wildlife.

We slither past trucks and excavators – the dual-motor Polestar 2’s four-wheel drive would have been handy, but our Michelin Primacy 4s hang on gamely – to Launch Pad Elizabeth, right at the tip of the Ness. Gingerly, we place the car where the rockets will ignite.

The site’s acute remoteness was a key reason it was chosen for the spaceport. The airspace to the north is essentially clear, and only brine awaits below. Mere metres away from us, the North Sea heaves and grasps at knurled granite. Worthy of Hugo Drax, it’s a ludicrously dramatic place to launch space rockets. For them, this really will be the end of the earth.

Here’s how to road trip around Shetland

The Shetland Islands are nearer Bergen in Norway than Edinburgh, but the overnight ferry from Aberdeen makes it a practical road trip destination for adventurous Brits.

We took the straightforward M90/ A90 to the Granite City, but the Old Military Road (A93) via the Cairngorms is a spectacular alternative.

NorthLink Ferries operates the 216- mile route to Shetland, with vessels running nightly in opposite directions and selected services stopping off in between at Orkney. The direct journey lasts about 12 hours and is timed to take in dinner and an early breakfast.

We travelled up the spine of Shetland on well-maintained A-roads that had mostly single-track B-roads leading off them. Council-operated inter-island ferries are frequent, swift and cheap – we paid £21.70 return (car and two adults) for the two crossings needed to reach Unst.

Our route barely scratched the surface of places to see on Shetland, which include a surfeit of jaw-dropping landscapes, beautiful coastlines, otherworldly Norse ruins halfconsumed by nature and oddities such as Sumburgh airport, were the A970 bisects the runway via a level crossing.

For EV drivers, all Charge Place Scotland sites across Shetland offer completely free charging, including a handful of rapid chargers.

Why Shetland is the home of tidal power

Tidal power offers a more reliable source of clean energy than wind, wave or solar as it works on predictable six-hour cycles. The principle echoes that of wind turbines, but because water is much denser than air, tidal turbines produce more power from an equivalent-sized rotor. They have the added advantage of being hidden from view.

The marine turbines at Bluemull Sound are built and operated by Edinburgh-based Nova Innovation. It installed a 30kW prototype turbine there in 2014, then established an array in 2016: a world first. The site now consists of four 100kW units, with two more on the way. They have a blade diameter of 8.5 metres and leave a minimum clearance to the water’s surface of around 15m.

A 500kW Tesla battery station controls supply of the power generated by the array to the local grid, and Nova Innovation’s latest direct-drive turbines can each make 720kWh in a day – enough to power 72 homes or cover 3100 miles based on our Polestar’s WLTP range.

The company has overseas sites including Canada and Indonesia, and is currently planning a new, 15MW array at the opposite end of Yell that’s predicted to generate enough power for one-third of Shetland’s homes.

Source: Autocar