Nothing currently hampers vehicle production as much as the flow of semiconductors

From economic downturn to the semiconductor shortage and new sales models, we explain the year’s top issues

As the industry recovers from pandemic shutdowns, every stakeholder is looking for their place going forward. We have learned so much and believe this new knowledge will alter the landscape. Many things will change, but some will not evolve in the ways that conventional thinking would have us believe.

In the history of the automotive industry, notable landmarks denote waves of changes. Packard’s H-pattern shifter, Cadillac’s self-starter, Ford’s moving assembly line, Oldsmobile’s Hydramatic transmission and DAF’s CVT all changed the industry for the better, leaving hundreds of other dead ends in their wake. The industry is in the early stages of another revolution that will accompany many industry-changing technologies and strategies alongside ambitious attempts that will not gain traction – and it will take years before the difference becomes obvious.

Near-term industrial shifts toward electric vehicles are changing the passenger car and light truck right now. Further down the road – a bit further than the industry believed just a few months ago – will be full autonomy. And even further out will be the shift to fuel cells or something even better. Being prepared for the certainties of change and the risks of what that change will be will separate the winners and losers, avoiding becoming a Tucker or a DeLorean as a footnote in history.

This story is an extract from the December 2022 issue of Auto Forecast Solutions’ monthly report. Auto Forecast Solutions is the only fully integrated solutions provider of vehicle, powertrain, drivetrain and electrification production forecasting, business planning software and advisory services to the global automotive industry. Click here to download the full report, or to catch up on previous months.

Economy

Global forces are building to generate questions about near-term economic conditions. Just as inflation around the world grew following the pandemic shutdowns, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted trade. Automakers building vehicles in Russia were immediately affected and that was compounded by sanctions against the country and any company doing business inside its borders. All of the major global automakers and suppliers inside Russia have backed away, reducing their income and dramatically affecting their assets as plants were sold or abandoned.

Ukraine played a key role in the global supply chain before the invasion. It provided wiring harnesses to automakers around the world, primarily in Eastern Europe, and the interruption of those supplies had companies scrambling for alternative sources of these important components. In the end, the disruption was temporary, but the resourcing of parts will make rebuilding Ukraine after the war tougher as automakers and suppliers will be even more leery of the region if Russia continues to covet the former Soviet republic.

In order to combat inflation, global central banks raised interest rates, stifling industrial growth. Money for investment had been virtually free for so long that markets had begun to take it for granted. In the past year, rates have soared, with the US Federal Funds Rate starting 2022 at 0.00-0.25% and ending the year at 4.25-4.50%, making borrowing far more expensive. These rates are expected to grow above 5% in 2023 as the Fed looks to get inflation under control.

While vehicle sales should not be directly hit by these rising rates, buyers will find other parts of their life more expensive, leaving less to spend on new vehicles. Automakers with captive finance arms have always been able to set their own interest rates as part of their incentive packages. Even in times of high interest rates, automakers have offered buyers loans with interest as low as 0%. Boosting sales through low interest rates goes only so far when buyers need to seek more money for homes and have to spend more on food and utilities.

Unstable economic conditions provide little encouragement for buyers to look at purchasing new, or even used, vehicles, and that will slow demand over the next year or so. Although currently calling for an improvement in the 2023 North America production outlook, the threat of a deeper recession and continued rate hikes are creating an AFS forecast scenario in which recovery may be pushed out an additional 12 months.

Supply chain

Interrupting the flow of wiring harnesses from Ukraine was just part of the recent supply chain troubles. Following the semiconductor shortages in the automotive industry and beyond has been a guilty pleasure among market watchers for two years, but the struggles don’t end there either. Globalising the automotive supply chain over the past few decades boosted the profits of manufacturers and suppliers. Finding the lowest-cost sources of labor and raw materials allowed prices to be stable on aging technologies while high-tech navigation, infotainment and vehicle control systems have flourished, boosting profitability of vehicles. That was until outside forces disturbed the flow of these components.

A political swing toward localisation threw up walls between trading partners and previous free trade agreements were placed in question. Trade between the US and China had increased significantly since the 1970s, but growth of the Chinese economy and treatment of workers prompted Western countries to re-evaluate trade with the country, leading to trade barriers from the US, among others.

These moves dovetailed into the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic. After a year of shutdowns and finding ways to coexist with the virus, China focused on its plan of “zero COVID”, where any outbreaks would be immediately quarantined, shutting down factories, neighbourhoods or entire cities. Shutdowns inside China have persisted long after the rest of the world was vaccinated and living with lesser effects of the virus.

China’s decision to close off affected areas interrupted the supplies of components needed for the manufacture of many global products. For the automotive market, many manufacturers rely on parts sourced from China due to the lower labor costs and expansive industrial support network built over the past two decades. Among other regions, production of vehicles in Japan have been halted numerous times due to the lack of Chinese-sourced parts.

The China example is just one of many fragile areas of the global supply chain. With stockholders becoming more and more important in the direction of companies, stabilising the flow of parts is vital to improving the value of automakers and suppliers. China will continue to be a key source of parts, but many components are being analysed for a better balance of cost of labor, cost of raw materials and stability of the relations with the source country.

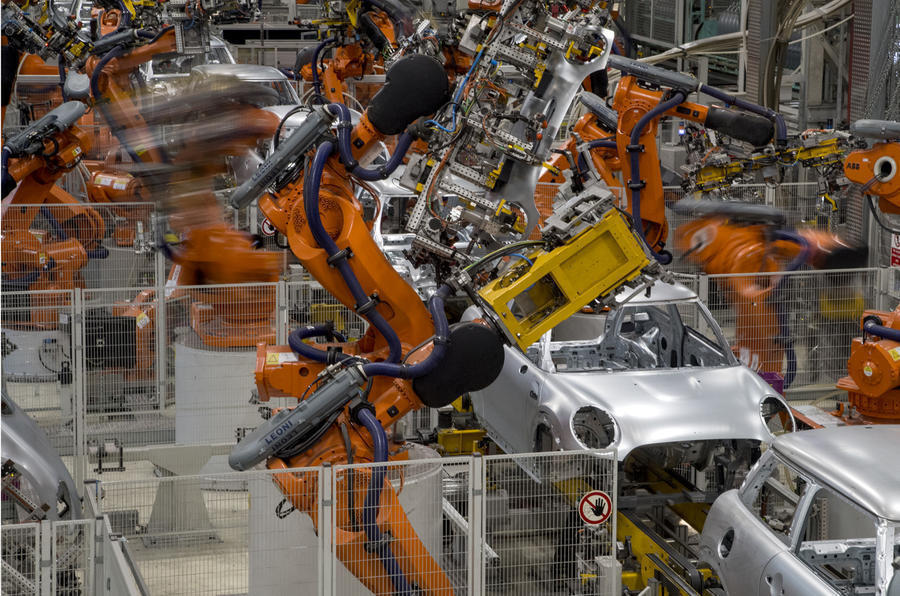

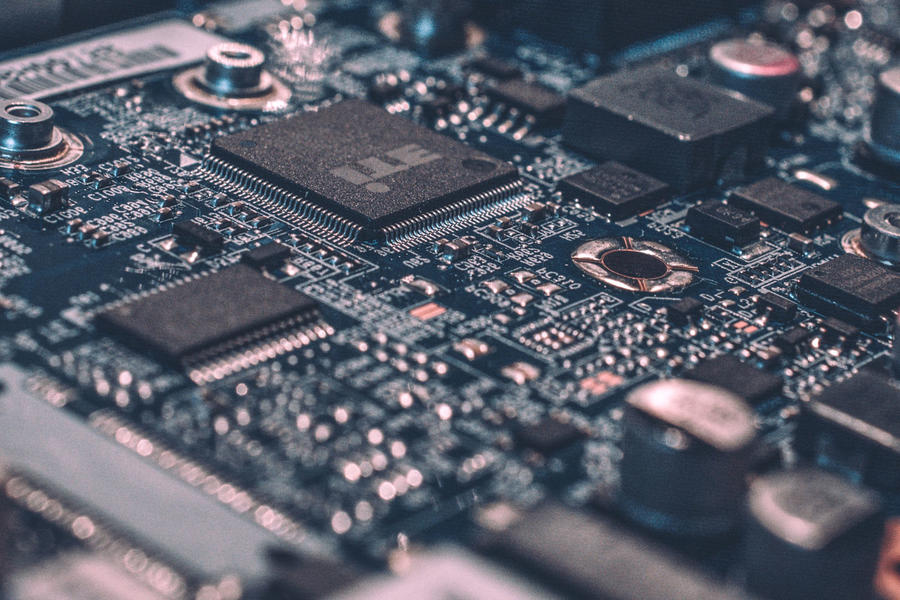

Semiconductors

Although other supply chain issues still exist, nothing currently hampers vehicle production as much as the flow of semiconductors. At the start of the pandemic, many different components became scarce and raw materials or labor issues occurred, due to COVID-19. As time went on, vehicle assemblers and parts suppliers found ways to overcome these issues, along with the pandemic subsiding significantly. The tight supply of semiconductors shifted to other industries as the automotive industry stepped out of line, believing that it would not quickly recover from the shutdowns. They were wrong and they were sent to the back of the line. Unused to playing second fiddle to anyone, the auto industry looked for more chips but that required more capacity. Building a facility to make semiconductors involves tens of billions of dollars. Spending that much money on a new fab usually means making products with the latest technology. Chips used in the vehicles affected by the original shortage are of older designs and these lower-profit chips don’t take priority when new plants are built. So the shortage of those chips is here to stay, forcing the industry to look at newer chip designs. Automakers know this.

When the shortage began, automakers had a chance to engineer out this issue but largely they have not. Some new BEVs use newer chips, but the traditional, older vehicles haven’t made the migration yet. That has given vehicle assemblers the ability to limit less profitable vehicle production in favour of higher-value models. This shrinking production reduces the required workforce in preparation for future BEV production needing fewer workers. The reason for this direction is blamed on an issue that has no real villain, which provides a “get out of jail” card for workforce reduction.

Focusing on profits now provides more funding in the transition to BEVs. With the first wave of electric vehicles lacking profits, this temporary windfall helps as tighter emission mandates continue to push for the electrification of light vehicles, leading toward eventual cost reductions and profits.

Electrification

A future propelled by electric vehicles is virtually certain. The need to reduce the pollutants emitted from motor vehicles has added so many emission control devices that today’s petroleum-fueled vehicles produce a tiny fraction of the pollutants that their predecessors did just half a century ago, but motor vehicles still generate a substantial amount of the world’s greenhouse gases. Shifting to battery-electric vehicles is the next step to reduce this output.

However, the transition to zero emissions is not without some peril inherent with adopting new methods of producing electric vehicles. The typical supplier-OEM relationship isn’t sufficient to keep up with evolving market demands motivated by changes in electric vehicle technology and evolving consumer tastes. Tesla’s in-house component design and production capabilities demonstrated the benefits of being agile when reacting to market demands. Tighter control over component specifications, especially those unique to the brand, shorten both production and validation time compared with the traditional model. This was never more evident than during the depths of the chip shortage, when Tesla engineers shifted away from the standard and scarce 7nm automotive component chip to the more modern 5nm chip and barely missed a beat. Agility in overcoming supply chain disruptions is a key component of future success.

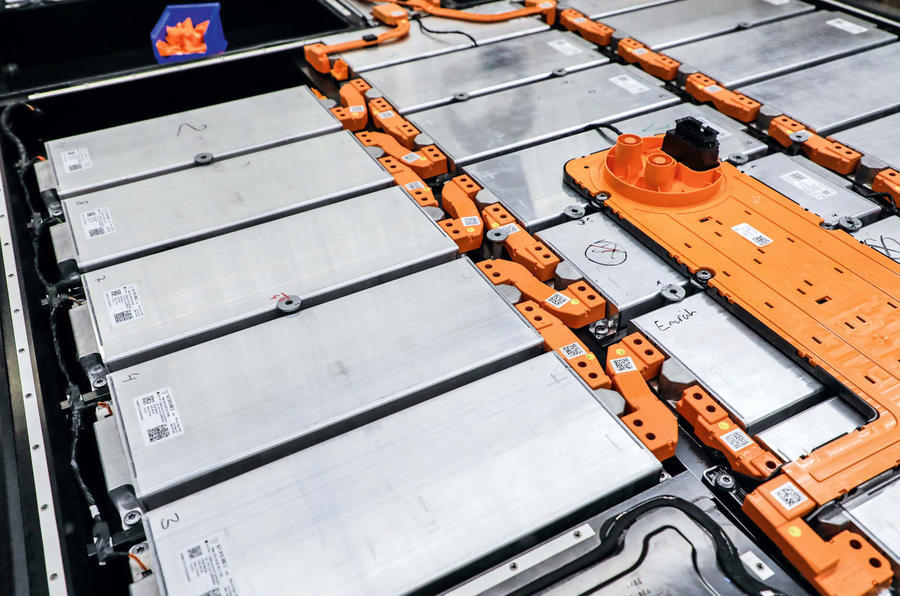

Battery cell production is vital to the production of future electric vehicles. Joint ventures between battery cell makers and OEMs are the business arrangement du jour, spreading the financial risk between the partners. Platforms with their electric motors attached, otherwise known as skateboards, are designed with standardised form factors, although the cell’s chemistries have characteristics unique to the particular OEM being supplied. Battery-side partners work closely with OEM engineers to optimise cell cathode chemistry and behaviours when connected inside the pack. Supplier issues with future battery systems are unlikely to be tolerated by customers, as evidenced by LG Chem’s defective cells in Chevrolet Bolts. The Bolt’s production volumes are returning, but slowly as customers come back to the market and reappraise the Bolt’s value proposition.

Battery cell development is currently centred on lithium ion batteries. The minerals contained in those cells are scarce due to limitations on extraction and refining. Added to that are political constraints such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the US. AFS expects battery-electric vehicles (excluding hybrids) to comprise 5.9 million units, or 34%, of North American production volumes by the 2029 calendar year (CY). That would call for battery cell production capacity to achieve over 500GWh per year. Counting existing and near-future battery cell factories announced for North America but not yet operational, approximately 320GWh of supply will be online by 2026CY.

Even with continued on-shoring of battery cell production, lithium ion cell supply will be a close call. The sources of lithium carbonate and spodumene needed from which to refine battery-grade lithium and battery minerals will form their own bottleneck before 2030. While estimates of current and future supplies vary greatly, most mineral forecasters agree that there will be a shortage of refined lithium, conforming to the IRA’s requirements, beginning by 2026. It takes five years to permit and bring to operation a brine pool evaporation project to produce lithium carbonate for refinement. It takes eight years to bring a hard-rock spodumene mine into operation from the permitting date.

Battery price parity

Most proponents of electric vehicles talk about price parity, which is the point in time when a vehicle with an internal combustion engine and a comparable battery-electric vehicle will cost the same. The idea is that increased battery production and the associated economies of scale will force battery costs down and bring the two vehicle types closer in price. Not only has this not happened yet, but the target date for price parity keeps being delayed.

Price parity was initially supposed to have occurred in 2020CY, then in 2022CY, and now it is being pushed back to around 2025CY. This is happening because battery costs have not been easing as the proponents expected. Economies of scale have been realised but that factor isn’t as strong as it was expected to be. Continued improvements will bring these costs lower but the reductions will not be significant.

Battery costs are actually starting to rise because of the scarcity of raw materials. As the demand for lithium-based batteries has soared, the availability of some of the raw materials has not and that is causing shortages. It takes several years to increase mining capacity for these materials. With supply creeping up slowly over the next couple of years and demand roaring, battery prices are expected to rise significantly during 2023CY and 2024CY.

New raw material capacity is expected to come online in 2025CY and through 2026CY. After that happens, battery prices should drop significantly to the levels of early 2022CY. The result of this will have some impact on electrified vehicles, on a global scale. Prices for BEVs will increase through 2024CY, slowing demand and production. We may not see an actual plateau, but a bit of a dip in the growth curve should be expected. As we move into the post-2024 era, BEV prices should become more digestible. The growth curve at that point should become much steeper, settling down around 2027.

While all of this is occurring, the average cost of new vehicles will continue to increase. The industry focus on higher-profit models due to production limitations has pushed the prices of ICE vehicles up, which actually moves the price parity point closer while BEV component prices, and the necessary rise in BEV prices, are working against this market shift. Finding a way to make BEVs profitable will be important to long-term industry success.

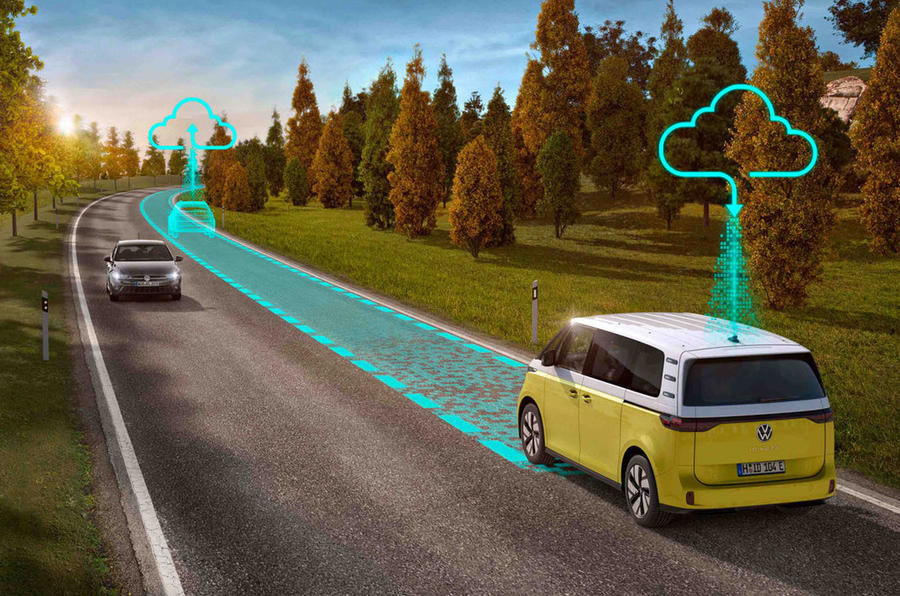

Software

Software is another OEM key to success, now and in the future. The Volkswagen Group’s CARIAD SE was formed to create the group’s software and solve the problems caused by existing vehicle operating systems, which have become a conflicted web-work of patches. The agile production methods introduced by the new hires from the software industry failed to take hold in the larger organisation. The results were a revolt within the organisation, a change in CEO, and a step backward with the Volkswagen ID 3 and ID 4 models already in customer hands. The bugs in existing vehicles are slowly being worked out, although Volkswagen still cannot update vehicle software over the air, as can some rivals. Properly addressing the software issue will break the winners from the pack going forward.

Future issues on the horizon are largely continuations of the existing headwinds. OEMs need to come to terms with how they approach the role of software in their organisations. Farming out operating system development to third parties cannot continue if a legacy OEM expects to transition into making software-defined vehicles (SDV). The unwary OEM could be tempted to trade away control of screens and access to vehicle/occupant data to Google or Apple in order to cut costs. Taking that bait could lock an OEM into a downward development spiral where an outside firm controls the experience with the vehicle. The time required to build competency in software development goes well beyond merely hiring more software engineers and requires a shift in attitude and perception of the entire organisation. A realisation that derailed Volkswagen’s path to developing SDVs and other legacy OEMs has yet to be recognised.

Autonomy

![]()

Technology and electrification are obviously joining forces to bring about autonomous vehicles. Raising the levels of autonomous control is improving the safety of passenger vehicles, with crash avoidance, parking assist and lane keeping, but creating fully autonomous vehicles is far more difficult than early entrepreneurs first thought. This gap between technology and reality has pushed Argo AI out of the field and delayed the launch of Apple’s planned autonomous vehicle.

TuSimple and Waymo are among the other companies focused on autonomy who have downsized or moved their attention elsewhere recently. Once the technology has caught up with the dream, regulators will need to update the laws to allow such vehicles to exist on public roads. Full Level 5 autonomy, where vehicles control everything without any driver input, will not arrive before the next decade.

More competition

In an interview with Automotive Industries about two decades ago, industry legend Bob Lutz explained how the industry would progress and allow for more competition. General thinking before this held that building motor vehicles, by their nature, was expensive enough to keep out new players. As the 20th century approached its end, the industry was driving toward a small handful of global players dominating the market, with a few niche players picking up the scraps. But Lutz was right for two reasons: one he foresaw and one he overlooked.

At the time of his interview, Lutz was working to revive the Cunningham sports car marque. In its asset-light approach, Cunningham designed an all-new vehicle but looked to someone else to assemble it. Pre-dating Lutz’s involvement, Cunningham was being developed as a “virtual car company” where it would own the product but outsource almost everything else.

Companies like Magna Steyr and Valmet provide a way to produce vehicles when a manufacturer doesn’t have the factory space or can’t find a way to make low-volume production profitable. Outsourcing vehicle assembly helped get the European Chrysler Voyager, Peugeot RCZ and Saab 900 Convertible into production. While major manufacturers use this method to make niche models, the same process is helping get models from startups on the road.

New players like Foxconn jumped into the market, providing assembly space for emerging electric vehicle companies. Leveraging Foxconn’s plant in Lordstown, Ohio, production of the Lordstown Endurance pickup, the INDIEV One and Fisker PEAR has been fast-tracked. Other startups will take the same path on their way to vehicle production.

While these new players may see such outsourcing as an asset-light approach to production, that path does not bypass the need for adequate funding. Legacy automakers with strong balance sheets and seasoned executives have experience with higher interest rates and should weather the situation well. Many EV startups, however, rely on easy access to capital. Even Rivian, among the best-funded startups, recently laid off workers, rationalised its product roadmap and delayed the launch of its R2 vehicle in an effort to preserve capital. When interest rates were hovering around zero, finding venture capital was relatively easy, but this becomes much tougher as the market rates rise and only the strongest will survive.

The reason for industry growth that Lutz missed was China. In the late 1990s, the idea of China rising as a global player was being discussed, but it was largely focused on supplying vehicles for its home market. GDP in China in 1998 was $3,356 per person, so few people could afford a car. Today, that figure has grown more than sixfold while inflation has not quite doubled the cost of goods.

The rudimentary passenger car market of the 1990s has blossomed into a full industry with a dozen globally competitive automakers alongside more than 100 smaller vehicle manufacturers. State-owned companies like BAIC, Changan and SAIC have attempted to export their products, with limited success, and the lack of competition in Russia is an opening for these companies. Sales of SAIC’s MG brand have shown some strength with its electric vehicles, but the focus will be on the private companies. Established manufacturers Geely, Great Wall and BYD are working on global marketing plans. Geely expanded by absorbing other automakers for their brand names and manufacturing footprint. Great Wall, long believed to be a potential export powerhouse, is crafting a new design philosophy and new brand names in order to target European and American buyers. But it’s BYD that has recently taken the lead with its successful electric vehicles and footholds in Western markets. EV startups such as Nio and Xpeng should not be overlooked in the rise of Chinese automobile manufacturing as they expect to be global players as well.

The sales model

![]()

When supply chain disruption slowed production, sales outlets were unable to fully stock their inventories. Lower inventories turned the traditional negotiation process further in the salesperson’s favour, increasing profitability for automakers and dealerships. Immediately, lessons were learned and it was announced that this was a paradigm shift. However, vehicle sales in much of the world rely on a broader system that can’t be controlled so simply.

In the short term, franchise dealers, primarily in North America, will carry fewer products. Reducing the stock will cost dealers less in financing and “floor planning”. Rising interest rates make large inventories of unsold products even more expensive, which pushes dealers to cut these costs where they can and encourages a smaller variety of demonstration vehicles. With less to wade through, buyers have less room to negotiate and have a higher propensity to order exactly what they want. It’s a win-win for people selling cars and trucks at a cost to the buyer. This, so goes the belief, is the future.

Capitalism, being what it is, will not allow this to happen unabashed. If there’s a void in the marketplace, such as customers looking for lower prices and/or a wider selection of products, someone will fill the void. The dealership network in the US has been built to ensure stores will be within a short drive of most Americans, and the older networks are so large that they compete with one another. This competition further lowers the transaction prices of vehicles, especially when a buyer can go a few miles down the road to the next retailer selling the same product. American franchise laws protect these stores from manufacturer-driven competition but also keep franchises competing with each other.

In the Automotive Industries interview mentioned earlier, Lutz ruminated on the nature of dealerships for his then-new automotive venture. Relaying a discussion with a friend about bypassing dealers, he said: “I told him that won’t happen, because he’d find it very difficult to add value – you can’t make the dealer go away. You’d need to find a factory that sells you cars directly.” Without knowing it, he was predicting the rise of Tesla.

“You’ve got this nationwide dealer-protection legislation in every state,” he explained. As Tesla is blazing a new retailing trail, the EV maker is finding that many states’ legislation prevents automakers from competing with its own dealers, but a question arises if a manufacturer has no dealers. Does the legislation mean a manufacturer can’t sell its own products in this case?

More and more American states are leaning toward startups and this could be a sign of a larger movement. Factory stores and factory-direct sales are not new but they are becoming the norm as Tesla expands its reach and new players such as Lucid and Rivian enter the market. Growth of these companies uncovers the flaw in the factory-direct model: service.

A network of dealerships provides factory-trained technicians to quickly and properly repair problems. When thousands or hundreds of thousands of owners need their vehicles checked for a quality issue, a local dealer can arrange the proper evaluation and fix with minimal trouble on the owner’s part. Over-the-air updates help with software issues, but when a component has a problem, someone needs to physically make the repair and this is where dealers shine. Finding alternatives for the startups is important to the long-term survival of these dealer-free companies.

As the dealer network evolves, an increasing number of transactions will work through the manufacturer. New agreements designed to retail electric models limit the inventory necessary for dealers and could transition stores into the paperwork processor. Franchise laws continue to slow this shift, but regulations will develop for dealers to remain competitive in the industry being outlined by startups.

An industry in transition

A year ago, the semiconductor shortage, the shift to EVs and the disruption of new players were the near-term issues facing the automotive industry and they remain very important today. Items that couldn’t be accurately predicted – such as Elon Musk’s foray into social media ownership and the associated fall in Tesla market value, Volkswagen’s move to revive the long-dormant Scout SUV and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – showcase the need to keep a constant eye on this industry. Expect more of the unexpected in 2023 but be prepared for the changes obviously coming.

Conrad Layson, Josh Sestal, Brian Maxim and Sam Fiorani

Source: Autocar