One of Polo Storico’s restored Miuras is an old prototype from 1971

The treasure trove of artefacts inside Lamborghini’s heritage division could grace any museum collection

“The name Rodrigo Ronconi corresponds to the truth,” says Rodrigo Ronconi, without unlocking his gaze from the data sheet of one very problematic Diablo. “Otherwise there is no truth,” he finishes, looking up through tortoise-shell spectacles.

Righteous words, but Ronconi is not an arrogant man. At least, he doesn’t seem arrogant in the three minutes I’ve known him. He seems industrious, very passionate and, frankly, like he could do without our surprise visit, although he hides it well. His Diablo issue is trivial but, at the same time, not. The owner needs part of the body repainted and wants it done yesterday. Tracking down the code for this ‘unique’ hue so it can be mixed afresh in Milan, and at great expense, has pitched Ronconi onto the trail of two Diablos from the early 1990s. The £160,000 question is: which one exhibits the correct paint code for our beleaguered owner?

As an archivist at Lamborghini’s Polo Storico department, this is Ronconi’s bread and butter. Time pressure, attention to detail, plenty of cash on the line. All the storied brands now have enterprises that service, restore, promote and authenticate their diasporas of heritage scattered around the globe, and Lamborghini is no different. The market for classics is worth around £1.78 billion annually (enough to buy every Porsche 911 2.7 RS in existence almost twice over) and so there is money to be made, but Lamborghini also seems to have strong altruistic inclinations.

The marque is still young and some of the existing staff were inducted in the 1980s or even the ’70s, not long after Ferruccio and Enzo fell out. Now is therefore the time to begin preserving the brand’s history and exploit the pool of lived experience before it dries up. Lamborghini is now so serious that it even consulted Porsche Classic, masters in the field of conservation, for advice when it established Polo Storico in 2015.

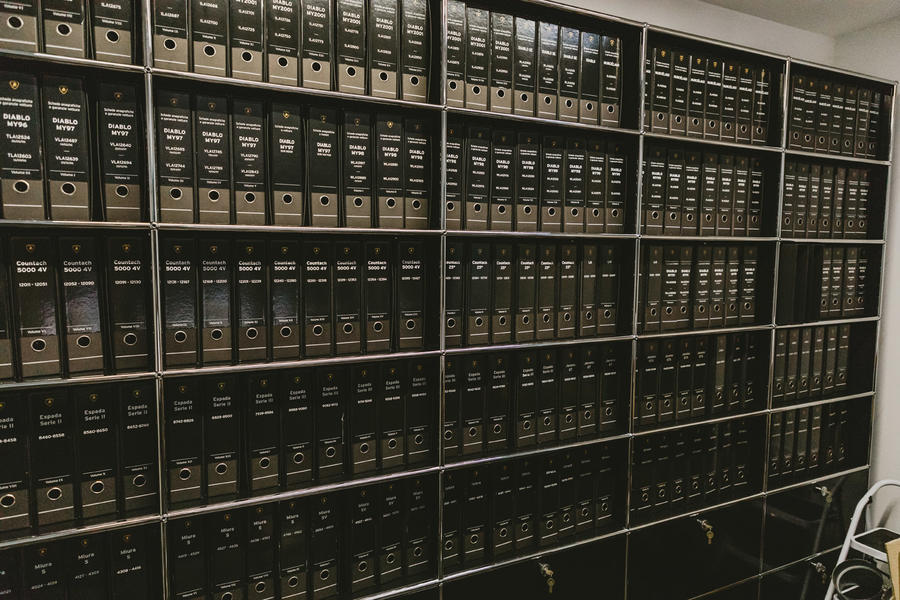

It remains a relatively small operation, not only because the department is younger than the Aventador but also due to the relative scarcity of Miuras, Countachs, Espadas and so on. Lamborghini built just 6900 cars between the initial 350 GT of 1964 and the very last Diablo in 2001, which is nothing. By comparison, Ferrari made around 60,000 cars during the same period and, by Lamborghini’s own admission, the internal library of photos and records at Maranello is astonishing in its depth. Jaguar, meanwhile, built 67,000 E-Types alone between 1961 and 1975.

But there is still plenty to do. The ‘truth’ Ronconi speaks of sits at the heart of the work Polo Storico undertakes when it isn’t forensically restoring cars like Miura SV chassis #4846 – the wondrous, perfect green machine pictured above – or making historically accurate spare parts. This work involves the awarding, or sometimes the withholding, of prized certificates of authenticity, which cost up to €10,000 (£8900) but can mean rather a lot more than that to an owner or prospective purchaser.

“Twenty-five years ago, you could find a Miura hidden behind other used cars at a dealership,” says Ronconi. And he isn’t exaggerating. Even in 2005, an unexceptional but sound SV sold for just £176,200 at Bonhams; today, a similar car would set you back around £1.5m. And alongside its current status as the most valuable car ever to wear the bull crest, Gandini’s masterpiece is also the model that causes the most severe certification-related headaches for Ronconi and co.

“They are the hardest. Some owners state that the modifications from early P400 or S [specification] to an SV have been done at the factory,” he says. “This is, in the majority of cases, not corresponding to the truth.” The chuckle as he says this gives away his love of the job: “Lamborghini did some upgrades on some cars – cars that had been heavily damaged – but we don’t have the data.” And the supposed word of the chief tester at the time, heard third-hand through your cousin’s friend’s gardener’s neighbour, isn’t going to convince someone like Ronconi.

Strictly speaking, even an endeavour as innocent as fitting SV wheels to an otherwise pristine P400 or using 215-section tyres to improve the handling (an early Miura uses 205-section rubber) is enough for Lamborghini to withhold the documentation. Harsh? Perhaps, but where else do you suggest they draw the line? That every different model has similar idiosyncrasies makes the job an investigative minefield.

Which brings us to the Comitato dei Saggi (the Committee of Wise Men). This intimate group meets ad hoc to debate and determine originality when the subject matter strays beyond even the considerable expertise of the archivists. It passes judgement in more complicated cases: for example, one concerning the front clam of a crashed Miura – one that was not restored by Polo Storico and that seems to have a repunched VIN on the new panel. Certification can be awarded to a car whose engine and, say, differential or body have differing numeric identities but are nevertheless each original, but you need to know your stuff to make that call.

The Comitato dei Saggi therefore consists of Lamborghini CEO and former Ferrari Formula 1 boss Stefano Domenicali; Lamborghini chief technical officer and father of the Bugatti EB110’s quad-turbo V12, Maurizio Reggiani; chief engineer for the Miura and long-time global motorsport tsar Gian Paolo Dallara; Mauro Forghieri, an engineer of extraordinary breadth and talent and the man to whom, aged just 26, Enzo Ferrari entrusted his entire racing operation; and the former head of Lamborghini’s offshore programme, Mauro Lecchi.

It’s a jaw-dropping line-up, for sure, and having your car assessed by the gang must feel like taking your driving test with Jim Clark in the passenger seat while Alain Prost and Lewis Hamilton confer in the back.

Ronconi now takes a moment to dig out some extra special paperwork, starting with the build sheet of the very first 350 GT development car. It’s truly extraordinary. Hand-measured cylinder tolerances are scribbled down, as is the 46 hours this V12 spent on the bench and its 6500rpm ceiling. We can read that it used Borgo pistons and an alternator from Bosch and that the compression ratio was a fairly conservative 9.5:1. These sorts of artefacts form the foundation of the archive and are gold dust for the archivists. “When I read some data made by the engineers – Paolo Stanzani, for example – then it means I’ve found a treasure. [We have] the very first testing reports of the first Miuras – Bob Wallace’s and Dallara’s thoughts. It’s just a few papers, but once you read them…”

Ronconi trails off, but his thinking is obvious. Polo Storico has arrived in the nick of time. This archive will soon find new premises, but for now there’s not even proper atmospheric control in the room where all this delicate paperwork is stored, and for years Lamborghini was frankly negligent, allowing its latest cosmic wares to shunt the marque’s heritage into the shadows. Yet Dallara and Forghieri are still only a phone call away, despite their pencil annotations appearing right here on diagrams that represent ground zero for the supercar as we know it. This realisation is as profound as it is humbling, and it seems that Lamborghini is finally seizing the opportunity to get its house in order.

“Okay, gentlemen” is our cue. For Ronconi, our stay represents 30 minutes he’ll never get back, but for us it represents an intoxicating insight into the Lamborghini time machine. As for the colour of that Diablo, the correct hue will be identified by a colleague in the paint shop; a colleague who has worked in the paint shop since the days of the Diablo, who possibly painted that very car and is now mere weeks from retirement. Like I said: it’s all happening just in the nick of time.

The other machines

In addition to its historic road cars, Lamborghini will provide a white ‘Historical Authentication’ dossier on, well, anything that has ever carried one of its mighty engines and is period-correct, including these eclectic machines…

Lotus 102 1990: Known mostly for its livery, the 102 is the only Lotus ever to use a 12-cylinder engine – and what an engine it was. For an F1 application, Lamborghini tuned its 3.5-litre V12 to deliver 750bhp and spin to 14,000rpm in race trim. Not that it ever powered the team to victory; driver Derek Warwick eventually described it as “all noise and no go”.

Riva Aquarama 1968: Understandably, Ferruccio Lamborghini felt he needed a glamorous aquatic runabout and so commissioned Riva to build him an Aquarama – only one that, instead of housing the usual twin V8 engines, was upgraded with twin 4.0-litre V12s born in Sant’Agata, each making around 350bhp. They sit beautifully exposed, with their bright-blue cam covers on display.

Murcielago R-GT GT1 2004: The Murciélago was never a natural fit for motorsport (although you wouldn’t guess it, its centre of gravity is high and its driveline is heavy), but the rear-driven GT1 was loved for the way it looked and sounded, both of which could be summed up as ‘pure evil’. Impressively, the 6.5-litre V12 was also strong enough to go racing unmodified.

READ MORE

New Lamborghini Huracan Evo RWD Spyder revealed

Driving a Lamborghini Murcielago with 258k miles on the clock

Source: Autocar