By burning coal, flammable gases would be sent through to the carburettors of the engine

Coal- and wood-powered cars, driving a lorry in the blitz, and an indignant Mercedes-Benz owner

As the war machine grew ever hungrier and merchant shipping ever harder, petrol became an extremely important yet very scarce commodity in Britain.

Fortunately, the government had foreseen such a dire scenario as early as 1937 and thus initiated trials of an alternative method of vehicle propulsion: producer gas.

This fuel was made by burning natural substances, mostly coal, derivatives thereof and wood. Flammable gases would be sent through to the carburettors of the engine as temperatures rose in the fire zone: methane (300 – 450deg C), hydrogen (700 800) and carbon monoxide (1000).

Tests on a truck showed that, on anthracite (hard coal), its six-cylinder engine produced only 40-56% of its best power, because the gas and air mixture had just 60% the calorific value of petrol and air. Admitting steam through the fire zone made no difference.

People at home would often see vehicles towing gas generators during the war: in Britain buses and trucks burning coal and in Europe, particularly Germany, all vehicle types burning wood.

Another wartime alternative to petrol was town gas (a by-product of coal coking used domestically), which, being uncompressed, had to be stored in an enormous bag in a frame on the vehicle’s roof.

Both had scary risks: explosion and carbon monoxide poisoning.

How does an Army Service Corps prepare for dangerous driving?

“Driving a lorry through the blackout into an area where a blitz is in full swing, into the hail of falling shrapnel on roads strewed with toppling masonry, fires raging and bombs blasting, is not a pleasant job, especially if your lorry is loaded with shells for an anti-aircraft battery.”

How was one prepared for such tasks, then? We visited a training centre of the Royal Army Service Corps to find out. Men were first trained as soldiers, going through foot drill, arms drill, weapons training, anti-gas drill and map reading.

Motor training then featured a number specific steps that had to be mastered in turn, lasting a minimum of five weeks. (Women were there, too, although learning to drive large staff cars, not lorries.)

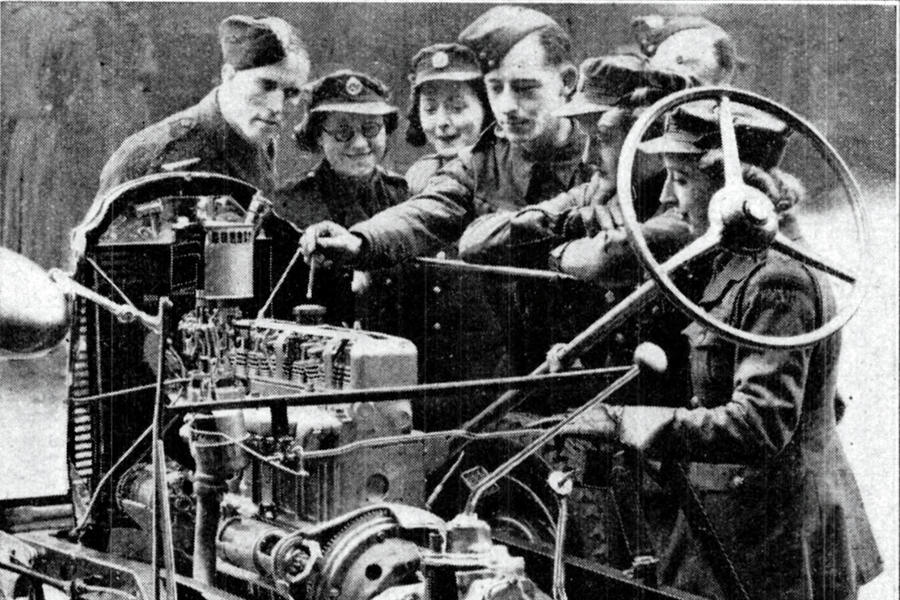

In one area of the camp was a large modelled road plan, used to explain the best practice in various situations. In another, a chassis donated by Vauxhall was used to explain the function and adjustment of parts (pictured). Elsewhere, parts were given for practising maintenance.

The backbone, though, was the daily task system: 16 maintenance tasks done across each of the 14 days. The course graduation test then contained 11 parameters.

Clearly it worked, as these men averaged only one incident, many just minor, every 40,000 miles.

A Mercedes-Benz owner defends his car’s reliability

We and our readers had made some unkind comments about Mercedes-Benz cars, and despite it “being a production of enemy origin”, one Broughton Parker felt obligated to defend his 290 cabriolet. Steering like a lorry? No way. Made of cheap tin? Absurd. It hadn’t gone wrong in 80,000 miles while being good for 70mph and not bothered by steep inclines, all while delivering 18mpg. Having owned 18 cars, Parker knew none that gave him such confidence and comfort, and in trying a small British sports car, he had longed for his 290, so rough was the ride. It still looked modern after six years, too.

Advertising the war effort

Supply restrictions recently have led car firms to almost stop advertising in print. Not so in the 1940s, when they instead bought space to highlight their war work. Rolls-Royce boasted of “the fine significance of its name” continuing in RAF aircraft such as the Spitfire (pictured); Alvis spoke of “supremacy and quality through land and air”, having turned its hand to armoured vehicles; Lagonda tried simply to inspire, rather than shout about its flamethrowers; and Lodge illustrated how its spark plugs were used in every kind of vital vehicle.

Source: Autocar