Tesla has its own ‘Supercharger’ network – it’s a big plus for owning one

What’s in an EV motor? How does regen work? Who is Chad Emo? We’ve got the answers you seek

Electric cars have been around since the 1830s. Sure, they might have disappeared for a bit, but they came back with avengence in the 2010s.

A decade ago they were pretty much the reserve of the well-heeled environmentalist, but the electric car’s viability has skyrocketed because of huge gains in electric range, and serious cuts to pricing.

However, car makers’ ability to actually explain how electric cars work has not grown with the increased enthusiasm for them. Think it’s too late to learn? Think again and learn the new lingo, here.

Electric motors

Literally the driving force of all EVs, electric motors are like jet engines in that they have few moving parts and are incredibly powerful for their size.

Mechanically simple, with just a rotor and stator, they generate power and torque using magnetic fields.

The most popular type of motor is the brushless permanently excited synchronous motor (PSM), which has powerful rare-earth magnets embedded in its rotor.

Surrounding stator coils (the static part) use an alternating current (AC) to generate a rotating magnetic field, which attracts the rotor’s magnets, making it turn in perfect synchronisation with the frequency of the AC. The rotor and magnetic field are perfectly in sync, hence the motor is synchronous.

Some manufacturers prefer to avoid the use of the rare-earth permanent magnets and opt for either asynchronous induction machines or externally excited synchronous machines (EESM).

Both the stator and rotor of an induction motor have windings and an electric current is induced in the rotor by the stator’s magnetic field rotating around it.

That in turn generates a magnetic field in the rotor windings. But for it to work, the rotor must lag behind the rotating magnet field slightly, hence the motor is asynchronous.

Externally excited synchronous motors instead use brushes to carry current to the rotor coils, which introduces an element of wear that brushless motors don’t suffer.

Regenerative braking

One of the great benefits of EVs is that they can recover some of the energy they use to accelerate when they’re slowing down again, because motors can also work as generators.

The motor switches to generator mode as the car slows down, topping up the battery, and the effort that takes creates a braking force.

Electronics blend the effect with the car’s hydraulic braking system if the driver brakes in the normal way. Strong regen allows one-pedal driving, where the driver can do most urban driving using only the accelerator pedal. Nissan was the first to make this a feature, on the Mk2 Leaf.

Other manufacturers, most notably Kia, have also added paddles to the steering column that allow the driver to increase and reduce the strength of the regen on the fly.

Battery packs

Electric cars have two electrical systems: a high-voltage one to power the motor and a conventional 12V one to work ancillaries such as the lights and infotainment system.

The high-voltage system traditionally works at 400V, but in some of the latest EVs it works at 800V. This higher voltage allows a lower amperage and so smaller, lighter electrical cabling, as well as enabling ultra-rapid charging.

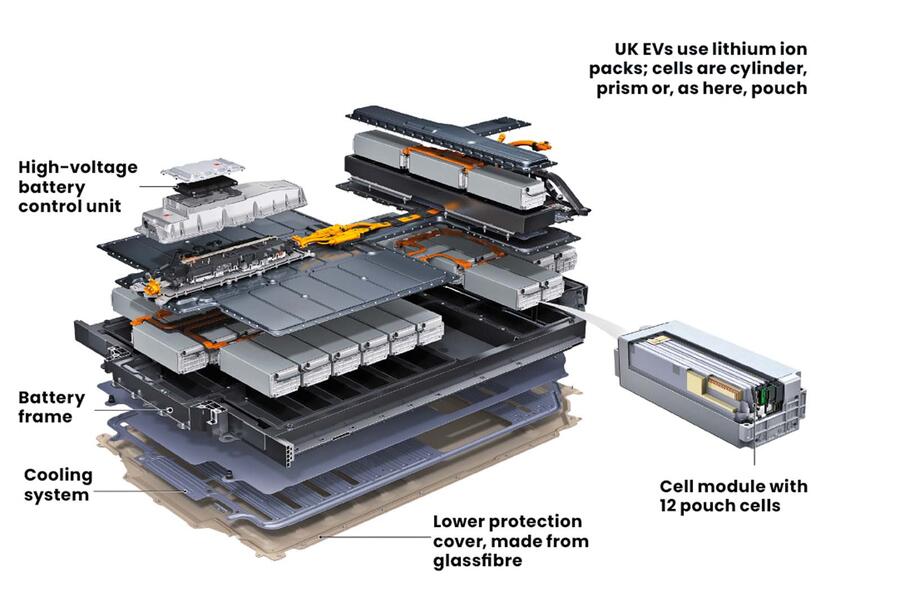

All production EVs on the UK market use lithium ion battery chemistry, but this in itself varies, with different ingredients used in the battery cells, depending on what the manufacturer chooses.

One of the most popular formulations has been lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC), but many manufacturers are trying to lessen their use of nickel and cobalt by reducing the content of the metals or switching to alternatives such as lithium iron phosphate (LFP).

Battery packs are made up of modules, each one of which comprises a number of individual cells. These come in various shapes, such as cylinder, pouch and prism.

The first wave of EVs had air-cooled batteries, but the latest models have liquid cooling.

Electric car range is affected by ambient temperature, driving style, air- con usage and more, and some EVs estimate their remaining range better than others.

Home charging

An EV works best in terms of running cost and convenience if you can charge your car at home. Drivers who don’t do many miles can get away with the trickle-charge lead that’s usually supplied with the car and plugs into a domestic three-pin socket.

It draws around 3kW (about the same as a kettle or household electric heater) so will top the EV’s battery up with around 3kWh of energy every hour, giving around 10 miles of range, depending on the car.

The alternative is a wallbox charger. These are available from a number of manufacturers and must be professionally installed on a dedicated electrical circuit.

They provide charge at around 7kW so boost range by around 23 miles each hour, depending on the EV.

Buyers can choose between an untethered cable, which must be plugged into both the car and the charger, and a tethered cable, which is stowed on the wallbox when not in use.

For those who have a solar system at home, there are smart chargers that offer a number of different modes, including the ability to charge only when surplus solar energy is available, which would otherwise be directed to the grid.

Scheduling and phone connectivity

You can configure an EV’s climate system and charging start and finish times by creating a schedule via the infotainment system and in most cases via a dedicated smartphone app created by the manufacturer.

Climate scheduling is especially useful if, say, you leave for work at regular times and would like the cabin preconditioned to a comfortable temperature.

Smartphone apps allow you to do the same thing on the fly, plus they usually have a number of other functions, like remote locking and unlocking, warnings if the car is left unlocked and status information such as available range.

Charge scheduling is also useful if you have a solar system at home and want your EV to start charging when excess power is available that might otherwise be sent to the grid.

Cheaper home energy tariffs

The ability to set schedules for when an EV plugged into a wallbox or trickle charger starts and finishes charging comes into its own when you subscribe to off-peak energy tariffs.

Several energy providers offer EV-focused tariffs of as low as 7p per kWh in the early hours, so you can plug your EV in but set the schedule to charge only during the off-peak time, which might be between 12am and 7am, depending on the supplier.

Using a 7kW home charger, that could give close to 195 miles of range at a cost of less than 2p per mile.

Plug types

Fifty years ago, an epic struggle broke out between JVC and Sony to dominate the home video tape market with their respective VHS and Betamax formats.

VHS eventually won, making Betamax obsolete, and the two names came to symbolise competing standards. EV charging plugs went the same way a few decades later, which is why there are different plug formats out there, causing some confusion.

The first Nissan Leafs came with a Type 1 ‘J-Plug’ for AC charging and a Chademo plug for direct current (DC) rapid charging, which was the standard in Japan.

Meanwhile in the EU, the Type 2 Mennekes plug became the standard for AC charging and the Combined Charging System (CCS) plug for DC rapid charging – so called because it combines the Type 2 plug with an additional two pins for carrying DC straight into the EV’s battery.

When you arrive at a public charger, Chademo plugs (if present) are easily identifiable as bright blue and CCS plugs as plain white.

CCS has become the VHS of the EV charging story, having become the dominant standard for rapid charging.

Even Tesla is moving away from its North American Charging Standard (NACS) connector: the Tesla Model 3 is now equipped with a CCS socket and its public Supercharger network now also supports CCS.

The plugs have so many pins because some are for communication between the car and the charger and others to actually transmit current.

When an EV is plugged in, the car and charger talk to one another and only when both ends are happy does the power transmission begin. The connectors aren’t ‘live’ until that point, which is why they’re safe to use in wet weather.

Type of charging

The thorny question of how fast an EV’s battery can be charged depends to some extent on how much power is available to charge it. There are four main generic categories of charger available: slow, fast, rapid and ultra-rapid.

Slow charging is the type used for home charging, with AC current coming from a trickle charger connected to a normal domestic supply or a 7.4kW wallbox.

Fast charging at 22kW with AC current is the least common and requires an industrial three-phase electrical supply. Ironically, it’s also not that fast, so it isn’t that useful when you’re on the move and need a ‘splash and dash’.

The first public DC chargers were 50kW rapid chargers. The latest is the ultra-rapid DC charger, which works at between 100kW and 350kW, depending on the charger and the EV.

Only EVs with 800V charging systems can take advantage of the highest charging rates. For example, the Hyundai Ioniq 5 N’s battery can be topped up from 10-80% in just 18 minutes.

Tesla has its own network of Supercharger sites, some of which have now been opened up to other EV drivers; you can find them via a smartphone app and pay to use them by credit card.

Paying for charging for an electric car on major rapid-charging networks is mostly contactless, but there are still exceptions.

However, the Public Charge Point Regulations legislation that came into effect in late 2023 requires that “all new public charge points 8kW and above deployed after 24 November 2024 and all public charge points of 50kW and above must offer contactless payment either per public charge point or per charging site, if more than one public charge point”.

Source: Autocar