In 1932, we asked four industry leaders what cars would be like in 1942

Back in 1932, Autocar asked some leading lights of the automotive industry how cars and driving were set to change

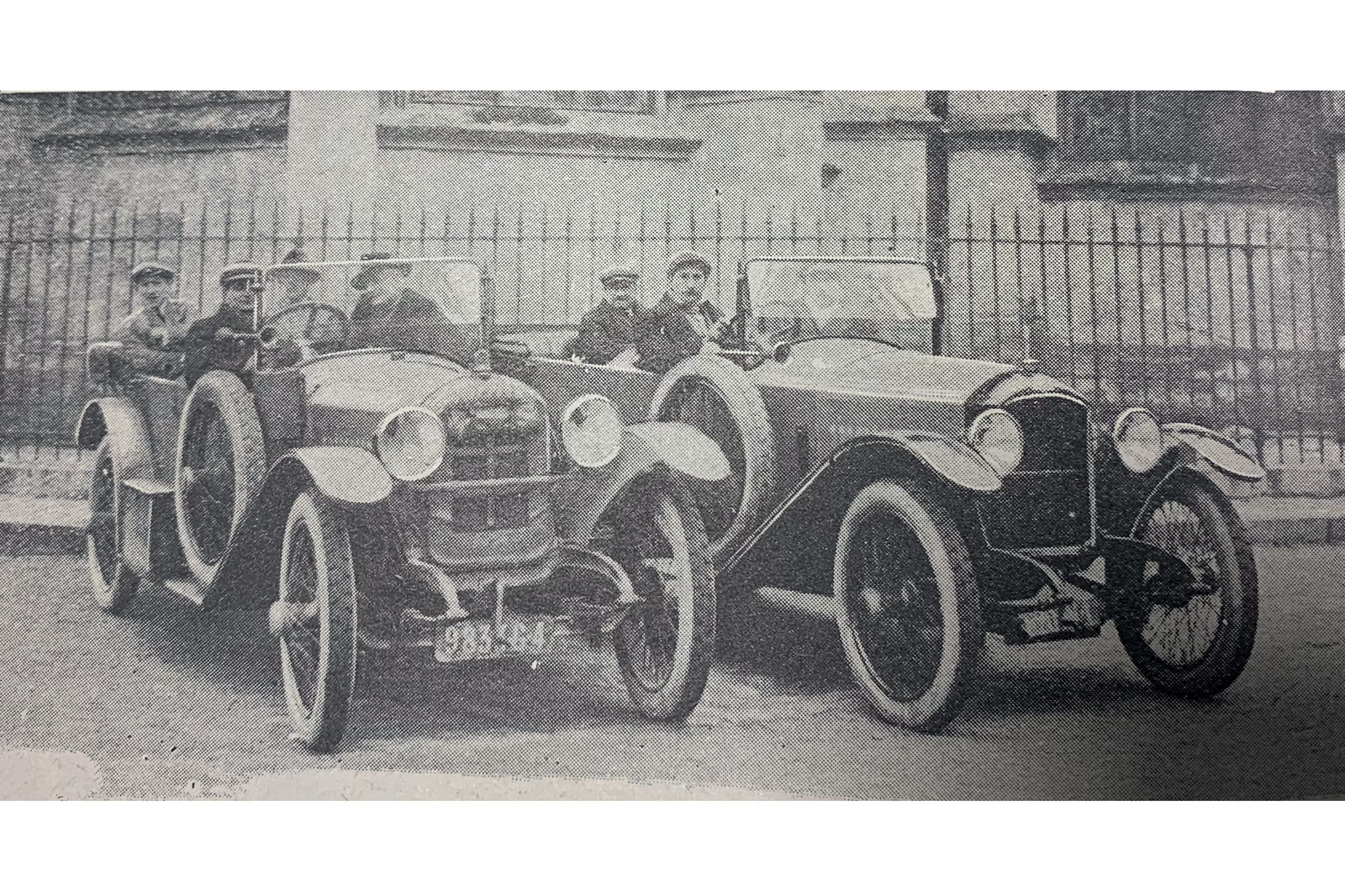

By the 1930s, the nascent period of the automotive industry was over, and companies were beginning to mature. Cars were no longer only accessible by the rich, and people began to wonder in earnest how things could progress.

So, in January 1932, Autocar interviewed four leading lights of the industry in Britain to find out what developments they could foresee occurring over the next decade, both to vehicle design and the nature of driving itself.

First up, and arguably most notable, was Laurence Pomeroy. Having studied engineering at university, he joined Vauxhall in 1905 and became technical director just nine years later. He joined the British Daimler company in 1926, having become a leading designer of engines. In 1934, he would be elected president of the Institute of Automobile Engineers.

Pomeroy’s predictions were conservative. “I can see nothing in the world of industry or the realm of science to indicate any more rapid change in design than has occurred in the past 10 years,” he said. “We are, of course, as an industry generally devoting a bit more time to transmission problems, engine smoothness, silence and the like, but these are merely ripples on the surface of the waters which you are asking me to plumb to their depths.”

He did, however, predict that vehicles would “tend to fit themselves better to human beings than they do now” and that “everybody who has a motor car will, naturally, desire that motor car to give him more luxury and performance than now. Thus will come about an increase in the size of cars, but with it also will come increased manufacturing efficiency, so that there will be only a small increase in cost, if any.”

Independent suspension had first been used way back in 1922, on the Lancia Lambda, but not yet become commonplace. Pomeroy was enthused by this develoment – crucial to the progression of cars beyond mere motorised carriages – he had seen in the recent work of Austro-Daimler and Mercedes. The latter had revealed its 170 family car the year before with transverse leaf springs for its front wheels and a coil-sprung swing axle at the rear.

Streamlining was also en vogue in the 1930s, seen most prominently in the designs of Tatra and the Nazi-era rekordwagens, and Pomeroy predicted this design style becoming widespread. An improvement in power-to-weight ratio – the “crying need of the time” – he also correctly foresaw, by means of engine supercharging and reduction in chassis weight through aluminium.

Our second interviewee was Arthur Hubble, the boss of Crossley, a Manchester-based manufacturer that made luxury cars from 1904 until the outbreak of World War II.

“It is possible to foresee the electric motor car which will collect its power from radiating stations placed in suitable positions all over the country,” he said, “the current being broadcast just as we broadcast wireless programmes today. There will be no smell, no noise, and power will be tax free.”

However, Hubble admitted that might be “going too far”, and said we could reasonably expect by 1942 to see a car with no gearbox and just one pedal. Engines would move to the rear, he believed (this would take off in the 1950s but quickly be consigned to history) and the compression ignition engine would be “in common vogue, even for baby cars”. He also could see car weight going down by 50% by the discovery of some new metal.

His most correct assumption was the introduction of arterial roads in Britain. These would “link up city to city,” he said, “and where you wish to avoid any particular town, a detour will be provided.” The average speed would be greatly increased, too.

Hubble’s thoughts on the improved road network were mirrored by Cecil Kimber, designer and director at MG. This would directly bring about a revolution in car design, he predicted, with the engine moving to the rear to reduce the front cross section of the car and a body designed on “true aeronautical lines” for fuel efficiency.

“We shall not have wings, lamps, running boards and spare wheels added to a body design more or less as afterthoughts,” he said. “The car will be conceived more as a whole, and I think it will have a bumper or fender carried all the way round as a safety factor.” He did not imagine, however, the move towards monocoque cars, despite this concept first being realised back in the 1910s, seeing instead the retention of steel girder frames.

Although the front seemed likely, he had doubts about independent suspension at the rear, because this would cause steering issues at higher speeds.

Kimber’s idea that “some form of hydraulic transmission will entirely dispense with the gearbox and clutch” was, however, wide of the mark.

Our final subject was Allen Herbert, managing director of Peugeot in the UK, and he was perhaps the most conservative.

“I imagine that manufacturers will adopt the more conservative policy of making perfect the details of present design rather than a policy entailing costly experiments,” he said. Thus the popular car of 1942 would still be front-engined and rear-wheel drive.

Herbert added: “The present unwise and too intense form of competition amongst manufacturers will give way to a more healthy variety, the result being that they will work in closer unison, and the public, although having to pay more for their cars, will have far more real value for their money.”

Standard fittings, he said, would come to include “pre-selective gears; single-point chassis lubrication; built-in four-wheel jacks; dual ignition systems; multiple carburetter systems with superchargers as standard; underslung chassis, giving a very low centre of gravity with much improved suspension; steel cylinder liners; and a host of other refinements at present only fitted to the more expensive type of car.”

Most presciently – and perhaps unsurprisngly, given the role of Peugeot as the pioneer of diesel engines in cars – he also said: “The diesel engine will displace the present petrol engine, although it’s unlikely to be in general use for pleasure cars in 1942. The diesel, in turn, is likely to be superseded by the electrically driven car, but this will probably be in the more dim and distant future.”

As a footnote, and amusingly mirroring sentiments repeated ever since, he concluded: “I should like to be able to look in prospect on the improvement made in driving in 1942. At the present time, driving is getting worse and worse, and many drivers seem to forget all they have ever learned in the way of manners. I should like the police to have the authority to suspend an offender’s licence until he has satisfied the authorities of his possession of an average amount of road sense.”

Source: Autocar